A few years ago, I got a call from a journalist friend. He’d just been assigned to do a Lance Armstrong cover profile for a major magazine, and he didn’t know very much about cycling. This was typical—the more you knew about the sport, it seemed, the less access you would enjoy, thanks to Armstrong’s army of PR flacks, agents, and protectors.

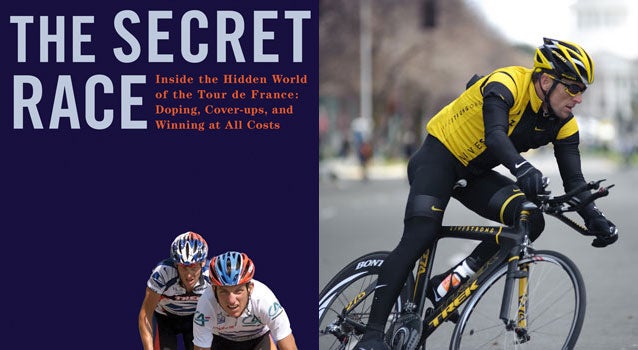

Dan Coyle co-authored The Secret Race with cyclist Tyler Hamilton.

Dan Coyle co-authored The Secret Race with cyclist Tyler Hamilton.

Dan Coyle co-authored The Secret Race with cyclist Tyler Hamilton.Then my friend asked the inevitable question: “What about the doping?”

I sighed, then gave him the rundown: the sad history of scandal in the sport, beginning with the EPO era in the mid-1990s and continuing through the Spanish affair called Operación Puerto, in which police raided the offices of a Madrid gynecologist in 2006 and found detailed doping plans and freezers and refrigerators full of blood bags marked with code names for dozens of top riders. One of those riders was Tyler Hamilton, who’d been caught, basically, with someone else’s blood in his blood. It was creepy, ghoulish stuff.

Then we turned to the subject of Armstrong. At that point, he’d steered clear of major scandal, but there were enough tidbits to suspect that something was not right: the positive cortisone test from 1999, the urine samples from that year that had supposedly tested positive for EPO when they were checked in 2005. All the teammates of his who’d gotten popped, who’d tested positive; the two teammates who had already confessed to The New York Times. The fact that he was working with Michele Ferrari, unknown in the United States but renowned in Europe as the master of dope-fueled training. Most of this stuff had been reported, in some form, in the press. Then it had disappeared.

My friend tends to write about quirky heroes of mainstream sports, with a sideline in damaged celebrities; he knows a thing or two about messed-up lives. We talked for more than an hour. Later he sent an email that said, “Cycling is CRAZY! Who knew?”

AS OF THIS WEEK we know a lot more, thanks to the publication of Tyler Hamilton’s memoir, , written with former ���ϳԹ��� editor . (Coyle was my first editor at ���ϳԹ���, before leaving the magazine in early 1990s.) Guarded for months with Manhattan Project–level rigor, The Secret Race is going to hit cycling—and the still unresolved Armstrong saga—like a bomb.

The Secret Race is not simply a rehash of Hamilton’s 2011 interview with 60 Minutes, as the initial Associated Press newsbreak suggested on Thursday. (The book’s release date is September 5, moved up from September 18, which awkwardly coincided with Armstrong’s birthday. The AP obtained a copy and wrote about it.) In fact, it’s the most comprehensive, detailed account to date of the culture of doping that prevailed in cycling during the Armstrong era. It’s a big, hot, steaming enema bag filled with purifying truth for a sport that has dodged it for far too long.

In 287 pages, Hamilton confirms most of the “allegations” that have “dogged” Armstrong over the years but could never be proven beyond a doubt. For instance: Have you wondered why Armstrong’s urine samples from the 1999 Tour tested positive for EPO? According to Hamilton, it was because Armstrong and his top lieutenants, Hamilton and Kevin Livingston, were all using EPO, the banned blood-booster drug (for which, incidentally, no direct test existed in 1999).

And remember Actovegin? That was the stuff that was in the trash bags that Postal staffers drove hours out of their way to deposit in roadside garbage cans in France during the 2000 Tour. They’d been followed surreptitiously by a French TV crew, who retrieved the bags and tested the contents. Actovegin, then an experimental drug made from calf’s blood, was known to improve oxygen transport. Yet Armstrong and Johan Bruyneel (director of U.S. Postal) insisted with straight faces that it wasn’t used for doping; instead, they offered a confusing story in which they claimed it was used to treat road rash and also a team mechanic’s diabetes. No explanation for why it had to be driven 60 miles out of the way and dropped off in a trash can, James Bond style.

According to Hamilton: Actovegin “was an injection that [team doctor Luis] del Moral gave some of the team just before a handful of big Tour stages, in order to increase oxygen transport, and which was undetectable in doping tests.”

But at the time, not only did Armstrong and Bruyneel escape any consequences, they managed to turn it around, attacking the French journalists for their purportedly tabloid-style tactics. The rest of the media pretty much bought it, and the Armstrong myth soon became unassailable. As did Armstrong himself: in his later Tours, it was not unusual to see the entire Postal team, nine riders churning up the steepest climbs in France, demolishing the rest of the field. It was like hitting 100 home runs in a season, and nobody looked askance.

And why would they? The myth was highly profitable, for the industry sponsors who saw their sales skyrocket and for the journalists who got book contracts and steady work covering the newly popular sport of cycling. One of the saddest sights of this new era, in fact, is the increasingly deep denial of NBC commentators Phil Liggett and Paul Sherwen, who are both friends of Armstrong and far richer because of his popularity.

But The Secret Race is much more than a laundry list of allegations or a score-settling diatribe against Armstrong. In fact, Armstrong only figures in about half of the book, in part because Hamilton left Postal after the 2001 season. It’s the story of a sport, and an athlete—Tyler Hamilton—gone astray. There have been other doping memoirs, beginning with ex-pro Paul Kimmage’s 1980s classic, , on up to British cyclist David Millar’s confessional , published in June.

Hamilton’s tale shows that doping has come an awfully long way since the steroids-and-amphetamines ’80s (the dark age that baseball’s dopers seem mired in), and unlike Millar, he names names and tells tales in a way that’s going to upset a lot of people still active in the sport. Among the willing participants in Postal’s doping program, he cites the beloved George Hincapie, Jonathan Vaughters (also called out for his “incredible” gas), and, by implication, Christian Vande Velde. Also dragged into the crossfire is former Team CSC director (and 1996 Tour winner) Bjarne Riis, who oversaw Hamilton’s transformation from beaten-down Postal lieutenant to a Tour contender in his own right.

THIS ISN’T ARMSTRONG’S STORY; it’s really Hamilton’s, the tale of an ex–ski racer who discovers that his true talent is for cycling—or, rather, for enduring pain. This lands him on the U.S. Postal Service team, which Armstrong joined in 1998, after his recovery from cancer. Gradually, he becomes friends with Armstrong, whom he clearly sees as a kind of complicated big brother figure, by turns kind and inexplicably mean.

The Postal team was driven by the win-at-all-costs mentality of team owner , an ambitious investment banker who was determined to get his Bad News Bears team into the Tour de France. Armstrong was perfectly in sync with his program, although (as Hamilton notes) the doping started before he arrived. They were getting pummeled by a doped-up European field, so the Americans decided to try and beat them at their own game.

Hamilton started with the “red eggs,” red gel capsules given to him by a team doctor supposedly to help with recovery; they contained Andriol, or testosterone. Then the doctor gave him EPO—which they called “Edgar,” as in Edgar Allen Poe. “We knew we were breaking the rules,” Hamilton writes. “But it felt more like we were being smart.” All of this was done under the eye of Ferrari, Armstrong’s personal trainer and doping doctor (who also faces a ban by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency). , who built a huge coaching business on his relationship with Armstrong, is barely mentioned. “During the years I trained with Lance, I don’t recall Lance ever mentioning Chris’ name or citing a piece of advice Chris had given him,” Hamilton writes. “By contrast, Lance mentioned Ferrari constantly, almost annoyingly so. Michele says we should do this. Michele says we should do that.”

The ethics of doping seem not to have troubled Armstrong. “To Lance’s way of thinking, doping is a fact of life, like oxygen or gravity. You either do it—and do it to the absolute fullest—or you shut up and get out, period.”

The crucial moment came during the run-up to the 2000 Tour, when Hamilton, Armstrong, and Livingston flew in Armstrong’s jet to Valencia, Spain, for a blood transfusion, which was performed by a team doctor in a hotel, with Bruyneel supervising. (Actually, it was blood removal; the blood would be replaced in the second week of the Tour, just as the riders would start to get worn down.) The transfusions were necessary because a new test for EPO had just been introduced. Blood transfusions using one’s own blood were still undetectable.

And also slightly disturbing. Hamilton: “With the other stuff, you swallow a pill or put on a patch or get a tiny injection. But here you’re watching a big clear plastic bag slowly fill up with your warm dark red blood. You never forget it.”

Then comes the inevitable falling-out with Armstrong—allegedly, Hamilton says, because Armstrong felt threatened by Hamilton’s growing strength as a rider. Cut out of the Postal doping loop, Hamilton claims he rode the 2001 Tour “paniagua,” his shorthand for the Spanish phrase pan y agua, “on bread and water.” Clean. The results back this up: he finished 94th. The next year, he was riding for Bjarne Riis at CSC —and challenging Lance for Tour supremacy.

DURING HIS 2009 COMEBACK, Armstrong summoned the British cycling writer Edward Pickering, one of his steadiest critics, to meet him in Austin, Texas, for an interview. The invite was supposed to mark a kind of glasnost in his relationship with the media. After the interview, out of the blue. He felt Pickering’s questions were “negative” and that Pickering felt he’d doped. He asked: “OK, then, if I cheated to win all those Tours, how did I do it?”

Hamilton has some answers there, too, starting with the bizarre tale of “Motoman,” a mysterious Frenchman who followed the Tour on a motorbike, carrying the team’s supply of drugs, syringes, and other paraphernalia. (Too bad they didn’t give him the Actovegin bags to dispose of.) Motoman turns out to have been a bike-shop owner from Nice who was friendly with Armstrong.

And while Armstrong defenders continue to claim that he “never tested positive,” it turns out that he did. “Yes, Lance Armstrong tested positive at the 2001 Tour of Switzerland,” Hamilton writes. “I know because he told me. We were standing near the bus the following morning, the beginning of Stage 9. Lance had a strange smile on his face. He was kind of chuckling, like someone had told him a good joke.”

Hamilton says he was appalled, but Armstrong strangely was not. “No worries, dude,” Armstrong said. “Were gonna have a meeting with them. It’s all taken care of.”

“They” were officials of the UCI, cycling’s governing body. And the positive test was indeed “taken care of.”

Later, Hamilton would get a vivid reminder of Armstrong’s pull with the UCI: during 2004, after notching some impressive results (including classic and at the Dauphiné Liberé), Hamilton was summoned to a meeting at the UCI. He was told by chief medical officer Mario Zorzoli that he’d delivered some unusual blood-test results and that they were watching him. A few weeks later, he says, Floyd Landis pulled up beside him in a race and dropped a bombshell: “You need to know something,” said Landis, then still riding for Postal. “Lance called the UCI on you.”

Which brings us to the great irony of this book: if Armstrong did call the UCI, he set in motion the chain of events that would lead to Hamilton’s positive test for blood doping. He did, in fact, have someone else’s blood in his blood, probably because of a botched transfusion. Hamilton was ultimately banned from the sport for two years (and, later, for life). But the call also led, in a way, to his harrowing confessional, which I believe.

I believe it for the following reasons. One, it fits the facts we already know (, for starters). Two, it’s incredibly, exhaustively detailed—far more than Landis’ revelatory emails, which started off the federal and USADA investigations in 2010. In his matter-of-fact, New England-y way, Hamilton lays it all out: how he got seduced (willingly) into doping, how it worked, how team doctors rationalized it (“This is for your health”).

The biggest cheat in the book is Hamilton himself. He makes clear that his transformation into a Tour contender was fueled by extensive use of blood transfusions. He also makes clear that doping does not equal a shortcut; for it to work, you have to train twice as hard. Otherwise you’re wasting your money—as much as $50,000 a season, plus bonuses paid to the doctors when you win.

AS A JOURNALIST, IT was really weird to try to write about cycling during the Armstrong era. I’d worked in “real” journalism in Washington, D.C., and then in Philadelphia, and I had interviewed drug dealers, murderers, soon-to-be-indicted con artists, developers, politicians, and worse. Nobody gave you less than a pro cyclist circa 1999 through 2005.

Coyle himself noticed it during his interviews with Hamilton. “When he talked about bike racing or the upcoming Tour de France, however, Hamilton’s personality changed,” he writes in an author’s introduction. “His playful sense of humor evaporated; his eyes locked onto his coffee cup, and he began to speak in the broadest, blandest, most boring sports clichés you’ve ever heard.”

Yep. Especially when it came to Team Armstrong, you got the feeling that everyone was guarding some sort of huge secret. Their dealings with the press were tinged, increasingly, with paranoia. They kept blacklists, enlisted other journalists to keep tabs on each other, and generally behaved like the Sopranos. Critics, starting with Greg LeMond, were dealt with brutally.

So it’s probably going to suck to be Tyler Hamilton for the next few weeks. Because he lied in the past, his credibility is going to be assailed. Armstrong defenders will call him bitter, a snitch, or worse; many sports columnists will line up for another round of righteous pontificating about Armstrong’s heroism, most unburdened by having actually read the book.

Don’t believe Armstrong’s supporters this time, and be aware that The Secret Race actually has a merciful undercurrent. It’s an “attack” on Armstrong only in the sense that it reveals many uncomfortable truths. But it is also an invitation of sorts. By making clear that doping was endemic to the sport, and that Armstrong was far from the only cheat, Hamilton leaves the door open for his ex-teammate and ex-friend to save himself. All it would take is a press conference.

The most moving parts of the story come at the end, when after years of lying to everyone Hamilton has to face up to the truth—and tell his mom. A few days later, .

“Here’s what I was learning,” he writes of that painful period leading up to his confession. “Secrets are poison. They suck the life out of you, they steal your ability to live in the present, they build walls between you and the people you love. Now that I’d told the truth, I was tuning into life again. I could talk to someone without having to worry or backtrack or figure out their motives, and it felt fantastic.”

has covered bike racing for many publications, including ���ϳԹ���, Bicycling, and Slate.