It's a 100-degree October morning at the sweltering end of the Dry, and I’m barreling down south of Darwin, the coastal capital of Australia’s Northern Territory. A roadside dial indicates that the fire danger is Very High. This is three levels below Catastrophic—not so bad. The landscape here alternates between conflagration and inundation. There are two seasons: the Dry and the Wet. The latter, a six-month period that can see as much as three feet of rain, should be arriving a few weeks from now. Roadside posts measure the height of flooding over the road during the Wet. The warning signs are higher than the hood on my rented 4×4. Nearly every truck on the highway has a precautionary snorkel coming off the roof to get air to the engine in a flood. Mine doesn’t, but that’s fine. I’m just glad the motorcycle plan didn’t work out.

Dinner?

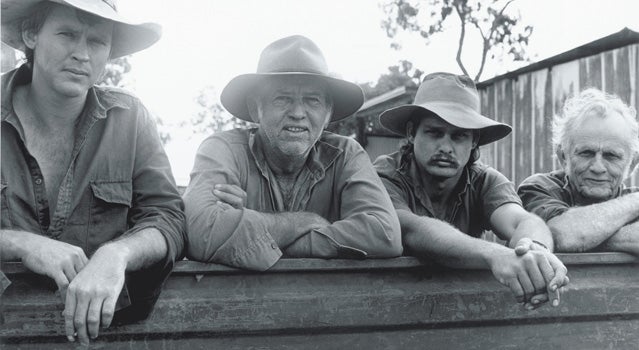

Arnhem land welcome

Australia’s Northern Territory, or NT, is one of the wildest landscapes on earth, an area twice the size of Texas with one-hundredth the population. It winds its way for 3,400 miles along Australia’s northern coastline, abutting the Arafura and Timor seas, and reaches 1,800 miles down into the heart of the country, a vast desert known as the Red Center. When my wife, Jess, and I looked into the idea of a road trip, we planned to ride a motorcycle 1,350 miles in ten days, from the coastal north to , the ancient 1,142-foot sandstone monolith, also called Ayers Rock, that’s the geologic heart of the Red Center. But the bike rental fell through, and that’s a good thing. This is not a place where you need to manufacture action. At a gas station, the headline on the local daily screams, “I DRANK MY OWN URINE TO SURVIVE!”

As I steer the 4×4, Jess reads the insurance waiver on our rental agreement aloud. It denies coverage of the following: anything that may fall on the vehicle’s roof or get tangled in the undercarriage, and any damage incurred by hitting an animal between dusk and dawn.Â

“Thrifty’s really covering its bases,” Jess observes. We head southeast, bound for the jungles of , passing the desiccated carcasses of cattle, wallabies, and buffalo hit by passing trucks.

SITUATED 130 MILES southeast of Darwin, Kakadu is twice the size of Yellowstone National Park. Its mangrove swamps, monsoon forests, and wetlands are home to 280 species of birds, 68 types of mammals, 120 reptiles, and 55 kinds of fish; its rock shelters hold some of the most ancient art on earth, 20,000-year-old Aboriginal paintings. During the Dry, most of the park’s creatures gather at billabongs, streambeds or pools that fill annually. After a miserable night of camping—pounding tent stakes into the ground was like hammering into a sidewalk, our single-wall tent managed to trap all the heat in the bush, and only an excellent Australian sémillon drank straight from the bottle brought any relief—we, too, make for the water. The Yellow Water billabong is a year-round network of floodplains, channels, and swamps. At a boat launch, Dave Darrington, a guide with salt-and-pepper hair and a fixed grin, beckons tourists. We climb aboard a 40-person aluminum boat and push off into the slow brown water.

Flocks of rainbow lorikeets hurtle past. A comb-crested jacana stilts its way across a skein of lily pads. Two big eyes rise to the murky surface, the pupils narrowing in the morning light. With a sweep of its crenellated tail, a 12-foot saltwater crocodile strokes alongside our boat, close enough to touch if you’re tired of your arm. Darrington informs us that these animals can jump six feet out of the water. Soon they’re everywhere, slipping down the banks and submerging like reptilian U-boats. The crocs were hunted to near extinction in the 1960s, but the population exploded after they were declared a protected species in 1971. Now they have the run of the place. A recent survey found 280 “salties,” which are larger and more dangerous than their freshwater cousins, in this billabong.Â

Soon, two adults begin thrashing on the far bank. One breaks free and glides slowly across our bow. There’s a ragged stub where its right front leg was moments ago but no blood—a crocodile’s circulatory system can divert blood flow away from missing limbs. I ask Darrington how long a person could make it in the water here. “About 25 seconds,” he replies.Â

The NT is a poor place for watersports. Saltwater crocodiles patrol the forested coastlines and can travel 100 miles inland along flooded waterways during the Wet. The beaches? Many are closed year round thanks to deadly box jellyfish, which can cause cardiac arrest. So you generally don’t swim here. But you really want to. The heat is visible, hanging in a thick haze.Â

By midday, Jess is scouring the map for relief. After a 25-mile drive up a washboard dirt road we reach Gunlom Falls, which pours 328 feet over a rocky escarpment into a deep pool. A couple of Aussie retirees in swimsuits cheerily tell us it’s safe—there are only mellower freshwater crocodiles in the vicinity. In the river below the falls, a huge steel croc trap has been baited with a rancid hunk of meat. We cut up a steep trail to the top of the escarpment, beyond the reach of the most adventurous reptile, where we plunge into a series of basins sluicing above the falls. The water forms a natural infinity pool looking out across Kakadu’s gum forests. Relief is that much sweeter when it’s hard-won.

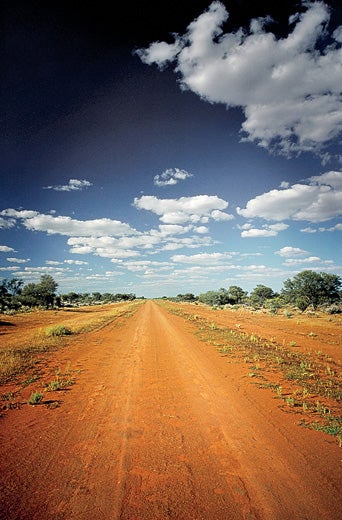

THE EXPLORER’S HIGHWAY is a postapocalyptic-movie scout’s dream. From Kakadu it unspools in a straight line, changing quickly from tropics to desert. In places, wildfires have raged through unchecked, leaving an eerie tableau of charred branches and giant termite mounds. Somewhere past Past Pine Creek, I press the radio’s seek button and the stereo scrolls endlessly. In place of music or talk radio or anything at all, Jess reads aloud from the journals of , a Scotsman who braved scurvy and boomerang attacks to explore Australia’s interior in the mid–19th century: “My powers of endurance were so severely tested, that, last night, I almost wished that death would come and relieve me from my fearful torture.”

Jess says, “Glad to hear it’s not just me.”

There’s little traffic except for the road trains. The highways in northern Australia are straight enough that the semis can hitch up three or four trailers at once. South of the dusty market town of Katherine, I pull up next to a road train at a weigh station and introduce myself to the driver, a tattoo-covered guy named Rod who’s missing his front teeth. Rod walks down his line of trailers, checking the pressure in all 62 tires by whacking them with a tire iron. He’s driving three trailers of mangoes nearly 2,000 miles to the southern city of Adelaide. At full speed, it takes him a quarter-mile just to stop. I ask if that presents a problem, with animals wandering out into the road. “You don’t even feel the roos,” he tells me. “The cattle you do.” Despite the long hours and mind-numbing distances, Rod insists that the life of a truckie is a fine one.

It occurs to me that the Australian preference for infantilizing nicknames— “truckie,” “brekkie” for breakfast, “footy” for their sadistic version of football—might be a linguistic defense mechanism for living in such a harsh landscape. This nicknaming trend has had unfortunate consequences. One of them can be seen pretty frequently on the Explorer’s Highway: the wedge-tailed eagle, or wedgie, which feasts on the dead kangaroos at the side of the road.

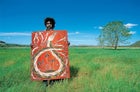

THE ABORIGINAL communities of the NT adapted to the harshness of life here over millennia, but their experience since the arrival of Europeans in the 18th century has been particularly grim. Aborigines, who make up one-third of the NT’s population, live, on average, 16 years less than whites. Poverty, alcoholism, and domestic violence are entrenched. Aborigines were not granted the right to vote in federal elections until 1967, but in recent decades the land-rights movement has restored some traditional homelands—including national parks like Kakadu and Uluru—to their Aboriginal owners. Key to this “native title” struggle was a 1992 decision by the High Court of Australia that overturned the doctrine of , which held that the Australian continent had been a no-man’s-land until the Europeans arrived. These days much of the NT’s economy is driven by tourists who come to see the art and culture of a group that not so long ago was treated as subhuman.  Â

Nowhere are these ironies more apparent than in , the tourist gateway to the outback. The Alice, as it’s called, is sheltered by the 5,000-foot peaks of the , and the city itself is filled with Aboriginal art galleries and some of the best Thai food outside of Bangkok. Dog Rock, an outcrop of stone that’s sacred to the local Aborigines, sits in town. You can visit it and then, if you’re hungry, walk across the street to the McDonald’s.

One evening we travel into West MacDonnell National Park with Bob Taylor, a local chef and guide. As night falls, we pull into a campground surrounded by ghost gums. After chopping up some mulga wood with an ax, Taylor starts a fire and prepares a multi-course fusion of Australian and Aboriginal “bush tucker” cuisine. Dinner is a terrific array of emu sausage with locally foraged spices and kangaroo fillets, medium rare.

Taylor has a sturdy build, with wavy, gray-tinged hair and a light brown complexion. In New York City he could pass for any of a dozen ethnicities; in Australia he was raised with a single abstract label: “colored.” Taylor’s mother is white, his father Aboriginal. A common government policy, even as recently as the sixties, was to remove mixed-race children from their families. Taylor, born in 1960, was a member of this “stolen generation.”Â

“There wasn’t a choice,” he says, turning the emu over the smoking coals. “Mom couldn’t do anything but console us. They didn’t have to arrest you; they’d just put the heavies”—the territorial authorities—“on you and they would move you.” When he was eight, Taylor and his three siblings were removed from their parents and sent to an institution in Adelaide. He didn’t see his mother for two years, his father for twenty.Â

Taylor is grateful for some of the education and opportunities he received from the white world—he trained as a chef in Adelaide and has worked all over the globe—but he feels most at home among the Aboriginal community. “Sometimes people will say mixed race don’t know where they fit,” he says. “I know exactly where I fit, mate. It’s my skin and my body.”Â

We dig into a miraculous dessert of pudding with quandong fruit and wattle (acacia) seeds. “Aboriginal people still have an opportunity, because we’ve got lands, to live in a traditional way,” Taylor says. For him, this means developing tourism that teaches visitors to respect the landscape. “They come to the heart of the country,” says Taylor. “They come to watch the sunset and climb the rock.” He means Uluru, our destination. “To Aboriginal people,” he says, “it’s a lot more than that.”

THE ROCK rears into view soon after we nearly hit a feral camel lumbering across the road. , named by an Australian surveyor in 1873, or Uluru, as it’s been called by the Anangu people since time immemorial, is the eroded remnant of a massive sedimentary slab thrust skyward some 400 million years ago. It rises 1,142 feet straight up from a sea of dunes and spinifex grass, breaching like a red whale. Uluru was deeded back to the Anangu in 1985, along with Kata Tjuta, a series of nearby sandstone domes. Both sites are key to the creation mythology of the Anangu. Upon receiving the land, the original owners immediately leased it back as a national park in exchange for a 25 percent cut of park entry fees.Â

At a gate near the eastern end of Uluru, we come across a sign that lays out the ethical dilemma faced by the 300,000 visitors who come here each year. Please Don’t Climb Uluru, it says in half a dozen languages. Before it was handed back to the Anangu, climbing Ayers Rock was what every tourist came to do. It has been a source of debate since the return, the traditional owners claiming it’s a violation, tour operators arguing it’s an economic necessity. There’s a plan to ban climbing in the next decade, but for now it’s merely discouraged. Still, about 100,000 people make their way to the summit every year, hauling themselves up a chain bolted into the rock at the steepest pitches. Three dozen or so have died—from heatstroke or, as one guide tells me, falling down “the world’s largest cheese grater.”Â

A smudge of boot prints traces up Uluru’s flank, and the Anangu contend that the lack of bathrooms on the three-hour climb has contributed to the contamination of the sacred water holes around its base. And the conflict over Uluru hasn’t exactly been defused by the antics of some visitors: a French woman who stripped on the rock and an Aussie footballer who .

The desire to distance myself from this kind of jackassery overrides the urge to look down at the world from on high. In the predawn hours of the next morning, we head to the far edge of Uluru and walk the six-mile trail around its base as the sun breaks the horizon. The rock is an astonishing interplay of geology and light, all red waves and folds. We say nothing, and we have the place to ourselves. And then we don’t. Reaching the base of the climb, we encounter a crowd of Japanese tourists. They stare balefully at the summit, which is closed to climbers due to high winds. Foiled, the Japanese have their photographs taken next to the CLIMB CLOSED sign. Then they clamber back into the comfort of their air-conditioned bus. We reach our vehicle and do the same. It’s mid-morning and already in the mid-nineties. Uluru is empty.