Of all the great travel narratives the most epic are set at sea—tossed in the waves, lost in fog, pounded by storms. They traverse a world populated by leviathans and ghost ships and bizarre natural forces, the landscape itself so moving and alive it becomes a character in the book.

Melville comes to mind with his descriptions of great tempests and great men, the “sweet mystery about this sea, whose gently awful stirrings seems to speak of some hidden soul beneath…” Joseph Conrad, Ernest Hemingway, Jonathan Raban and Nathaniel Philbrick were all taken by its spell and wrote about it in their books. They were all mariners, as was Joshua Slocum, maybe one of the greatest maritime authors—and for some reason the least known—who became the first man to circumnavigate the world solo in 1898.

��

Sailing Alone Around the World recounts Slocum’s three-year, 46,000-mile journey. (Read it free at Google Books .) ��It is candid and lyrical, self-deprecating to a charming, often hilarious, extent. ��It was written by an aspiring author and lifelong sea captain who was once marooned in Brazil—and spent six months with his wife and two sons building a “half Cape Ann dory and half Japanese [sic] sampan” to sail home on. (Voyage of the Liberdade recounts the adventure, also free .) Slocum climbed the rigging of his thirty-six-foot sloop, Spray, once when a rogue wave submerged the boat, outran pirates with a broken boom, warded off Fuegean natives by placing tacks—points up—on the deck and once sailed the Spray 2,000 miles across the Pacific without touching helm.

After his book came out, Slocum’s life became the subject of academics who thrive at taking apart anyone or anything that claimed to have set a record. A book out last fall by Geoffrey Wolff, The Hard Way Around (Knopf, 2010)��avoids the muckraking and simply tells the story of the man many have called the greatest mariner of modern times. Wolff writes about Slocum’s decision to attempt the feat—near the end of the Age Sail when steamers and steel hulls were pushing schooners aside, and sailor’s work was hard to come by—the love of his life, Virginia Walker, who bore him four sons at foreign ports and on the sea; his rise through the ranks of the shipping business and lastly, his mysterious disappearance at sea in 1908.

Slocum told his story throughout his journey, in dispatches and presentations around the world. Yet there wasn’t much fanfare when he returned to Newport, Rhode Island, on June 27, 1898. In fact, it wasn’t until he published his account of the journey a year later that Slocum’s was cast into the limelight. So when Reid Stowe broke the world record for the longest sea voyage in history last June—1,152 days without resupply; he saw land only once; lived for three years off food he packed; was at sea longer than the Essex on its ill-fated journey or Magellan and Shackleton combined—he found solace in Slocum’s trials and eventual success.

����

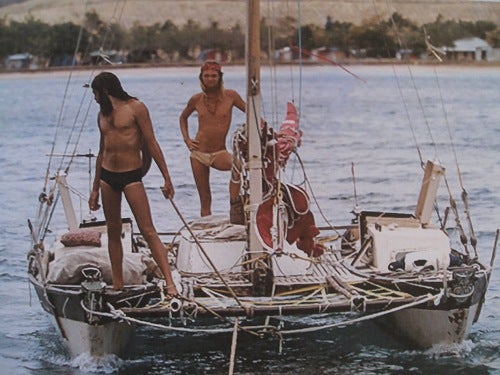

Stowe set out from the 12th St. Pier in Hoboken, New Jersey on April 21, 2007 on the 70-foot schooner, Anne, that he built with friends. His partner, Soanya Ahmad, joined him for the first 306 days until they discovered she was pregnant and she had go ashore—having setting the record for the longest continuous sea voyage for a woman. The story was covered on Reid’s blog, , and in brief updates in major news outlets. But after reports of his return—and his reunion with Soanya and their, then, two-year old son Darshen—he was quickly forgotten, and his story forgotten too.

Since then, 30 publishers have turned down the story of the longest voyage ever recorded at sea. Stowe has a best-selling ghostwriter working with him, and a top New York agent. Throughout his trip he was stalked by internet hacks who sent hate mail and criticized his spirituality and—admittedly—New Agey posts on his web site. It’s possible this factored into the publisher’s hesitation, as is the fact that they simply thought the story of a man sitting on his boat for three years wouldn’t sell.

I sat down with Reid and Soanya recently to talk with them about the difference between an adventure and an adventure story, the trials of the publishing world and the real reason he committed three years of his life to live on the sea in the first place. We met in the salon onboard the Anne, docked near 44th Avenue in Queens. The New York skyline reflected off the East River behind the boat. Reid and Soanya were preparing to leave the following day—they’d been asked to vacate the dock to make room for commercial traffic and were sailing to the abandoned New Jersey��dock they started their trip from in 2008.

Why did you take this trip? For the story, the voyage or something else?

RS: Because I love going to sea so much, and I always did. I never really cared about where I went. It was more about going on the boat and being at sea…It was really about what the sea did to me in a spiritual way, how it opened my mind and how it thrilled me with what it made me see.

Year after year as I sailed, I kept doing longer and longer voyages, and I never needed to stop. And I said this is what I like, why should I stop? By the time I was planning to go to Antarctica and I was down in New Zealand, I said what can I do next? And I said, well, I’ll just keep sailing at sea longer than anyone ever has.

SA: I learned about the project when I was still in school, and when I finished the degree that I was still studying, which was photography, I was thinking, where do I go next? I wanted to be on the water, but I wasn’t exactly sure where my niche was. I pursued another degree where I was looking at the possibilities of working on the waterfront in New York City and none of them seemed to fit me quite right. Then I met Reid and he was going to sea for this long period of time and that appealed to me more than any of the other mundane working waterfront kind of careers. Since I was at a crossroads in my life, I thought, this was something that I could really do, and that would be interesting, and I knew I would learn a lot from.��

When did you start thinking that this was going to make a great book?

RS: When I built my first boat when I was 20 and sailed that little catamaran to four continents and up the Amazon River. I knew I had a great story. I wrote it all out, I wrote the whole time. I tried to publish that story here in New York, back in the early ’70s, with the help of some friends. It didn’t work out so I went back to sailing—and saved the manuscript.��

I knew [our last trip] would be a great story before I even left. The longer that it took me to go, the more I realized it was the greatest story, there was nothing to beat it. Because everything everyone else was doing sounded like old news to me. They’re getting ready to celebrate a guy who’s going to walk across Antarctica, but they did that 100 years ago. Years before I left on this trip, I knew it was the greatest expedition of our era. I knew it was totally unique, was what no one had ever conceived of, no one had ever done. I knew it related to the growth of man’s consciousness. And the more hardships I had and the longer it took me to get ready to go, I said this is better than being a rich movie star. This is better than anything else. This is the greatest.

Stowe’s story on being caught by pirates in the Amazon��.

How did the criticism you were getting affect the trip?

RS: My friends started sending me some of the criticism, and I started to realize that every single thing I said [on my blog] was being criticized and contradicted. Different people and places were doing it. Even when I wrote a description of getting hit by a rogue wave and being turned upside down, I got criticism for that. And I’m thinking, “Well why do they hate me for that? I’m just telling them what happened.” And they think that I’m crazy. No, I’m not crazy, I was doing what a seaman should do, and I survived it like a seaman. [The boat] went complete 180-degrees upside-down and came back up again and everything stayed in place, because I had it secured. Nothing made a mess. Nothing changed in the motor room.

So, of course, I was influenced by people sending me emails saying, we’re waiting for you to die, we want to see you die. That’s why it might be hard for me to try to leave it out of the story. But because that stuff was happening, it’s partly the phenomenon of the internet and it’s partly that people could follow me live and it’s partly because my story got spread so wide, so fast, that suddenly that people were picking it up all over the world. My friends were looking at where the criticism was coming from, and one would be Nova Scotia and one would be the West Coast and some would be New York…it came from everywhere.

It’s partly the internet, because everyone who is doing it is doing it with non-names, with aliases. And they would be embarrassed if their family knew they were doing it or their fellow sailing friends, or whatever. I didn’t expect I would get criticism when I put on The Doors “Break on Through to the Other Side” and I started dancing—but people wrote me hate mail for that. They said, “You have the biggest ego, how can you stay on that boat?” And hated me and were calling me an egomaniac. And of course I thought, I don’t want to appear like an egomaniac, but I’m surviving out here. And I’m going on—and I’m always trying to present a positive, happy message.

Why are you having a difficult time getting a book deal?

RS: One of the things we noticed, about the time we were finishing the voyage, was a young girl who wanted to go sailing was getting world news all the time, again and again. Abby Sunderland, from California. This is something that everyone can discuss. Is a girl old enough or not? People can write into the blogs on the news and voice their opinion, and the news people are sitting there going, “Look at this, everyone’s interested, we gotta talk more about this, we gotta get something else on this.”

��

But what can a newscaster say about people who’ve been out at sea for nearly a year? The newscaster doesn’t have a clue what to say about us and the people in the audience don’t have a clue either. So it doesn’t become part of the discussion. We’ve done something so far beyond what people can comprehend, it doesn’t become a part of their discussion because they don’t get it, they don’t know what it is. One thing is for sure, if there were a small group of people in America who had been sailing for over 100 days, then they might be able to say something about what we’ve done, but I don’t know of anyone who has. One guy in America sailed 155 days. That was the record, he’s dead now. Dodge Morgan from Maine. But there isn’t even an American that’s done 200 days. So, when you look at going to sea for 306 days like Soanya or over a thousand like I did, no one has a clue about what I did, or how I did it. So how can they discuss it?

There are other similar stories that have made it big:��Eat, Pray Love. Soanya was with a publisher today who mentioned that book. And like I said, it’s a story of a middle-class person who had a divorce and then found themselves. Millions of people can relate to that. But who can relate to someone who is not coming back to the earth.

SA: It’s more than that. A lot of people don’t know much about the ocean. They can’t really think about it except what they’ve seen in the movies—which is storms and sharks. That’s all people know about the ocean, it’s really scary. So with those young girls, they’re not talking about “Is she capable of going to sea?” They’re talking about “Is she old enough?” Age issues are totally different than whether you have knowledge and experience.��

How did you feel at your meeting today, listening to your ghostwriter and editor talk about your story?

SA: Our ghostwriter has a pretty good grasp of the events of the story. He’s still new to my side of it, so we haven’t really spoken much. As for the editor, she was talking about it strictly from “how to sell a book” point of view. So it wasn’t, “Is this a great, real story?” It was more like, “Well, let’s see, the plot goes like this…that would not interest an audience in this way…it would have to be like this.” Everyone you speak to in real life, they are very interested in the story; they want to read the book. But when editor’s are trying to sell a book they’re trying to sell a story. They can’t make it up, obviously, because it’s a true story, but on the other hand some people might wish there was a bit more emotional drama in certain parts. ��

One point that she raised is if you leave society to go to sea for 1,000 days, it probably means, in the ideal novel, that you’re running from something or trying to get away from something. Or you just need some kind of change in your life and this is why you’re doing it. But in the real life story, I was just at a point where I was continuing an interest that I had. And so that’s not that interesting.

Another point she raised was, “You did this very consciously, and you seemed pretty together before you did and, upon return, you seem pretty together now. So we have to find where the change occurred over the course of time.” So there was this disjoint between how to tell a story that people will buy and how events happen—that is still interesting, but they might not get that because the editors don’t perceive that as interesting.

��

��

How do you envision the narrative arc of your book?

RS: If I were going to do the book, I would look at what I wrote, ever single day. Any way you look at it, one of these days I want to publish my logs into a book. But first I felt like I needed a mainstream book. And also I wanted a co-author, and money and I wanted it to be able to be made into a movie, so I wanted it written into that format. So I was hoping that would happen. And it still might. It’s a great story.

When I read The Perfect Storm I had a beef with it. And I had a beef with the movie too. Because what do people want? The story of a bunch of slack people who drink too much and hang out in bars and go to sea in an unseaworthy boat. I don’t like that story. And I don’t like that it was successful. It was a story of the sea. But I don’t think the characters were redeeming or interesting and I don’t like that kind of story. But it made it very successful and that might tell you what the audience in America wants.

Do you worry that people reading your blog or following your story would ever think that you did the trip for the book, for the money, for the movie?

RS: People have always been saying something like that. But you can’t risk your life for three years for something like money that you hope will come. I don’t think people go to war because they can make money or get a book out of it. That’s a hard way to make money. I don’t think you can sustain yourself out at sea with those kinds of wishes.��

The adventure story is a driver for an inspirational message that can go out to the world. That is part of what sustained me while I was out there. Because I had to look at myself and say, “What am I doing?” And if I felt that I was doing something good, for the world, then I felt secure.

Has the struggle that you have had publishing this story made you feel like an outcast?

RS: When I got back, the French writers who met us said, “You’re being ignored in America how do you feel about that?” Because if you were French you’d be a national hero going down the Champs-Élysées. By the time I got in, I knew I had been ignored by the press. I was getting letters from people during the voyage from people saying this is a travesty that the media has ignored you and written negative things about you.

I knew I would be an outcast when I was coming back to New York, because no one could even find a dock for me to even land on. They didn’t want me on any dock, to come in from the longest sea voyage in history. And so for the months, the half year before I arrived, I had everyone I know try to find me a dock and they wouldn’t let me come in. Then we were running around looking for places to go, and calling people and not getting answers from anyone.

The funny thing is, I’ve been back for a year and the same thing is happening to us now. We have to leave the dock we’re on, and we’re going to a place where we can be thrown out. And then we don’t know where we’re gonna go.

We have departed the touch of the terra firma longer than any humans and we did the longest sea voyage in history for a man and for a woman, and there’s no respect. The other boating captains that make up the life on the East River don’t want to know about us. You say to me why? And I say it has something to do with society, but I would ask “why” myself. How come they don’t wanna know something. I don’t believe that people don’t have minds that don’t follow the currents out of this river and know that they wind up in the sea and look at that horizon shining in the sun and not wonder what’s out there?��

–Porter Fox is the editor of . You can read more there.