Into the Wild Movie

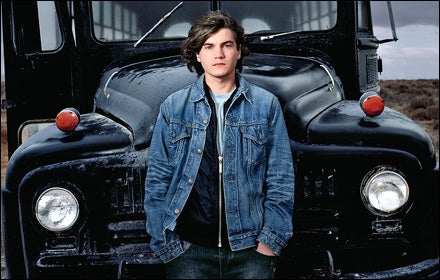

Hirsch outside Lancaster, California

Hirsch outside Lancaster, CaliforniaIt’s just 8:30 in the morning when I spot the nudists. ���ϳԹ��� the catering truck, I’m interviewing Into the Wild executive producer Frank Hildebrand when a white GMC Yukon rolls up to the parking area next to us and a leathery, hirsute man wearing a light-blue, knee-length bathrobe gets out of the passenger-side door. The wind blows, his robe flies up, and—whoa!

“When Chris was camped out here,” explains Hildebrand, “he was just up the road from Oh-My-God Hot Springs.” We’re standing outside California’s Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, a barren no-man’s-land of ocotillo-lined red-rock mountains and scorched bajada stretching to the desolate Salton Sea. “These people are extras in the scene we’re filming,” he says, before adding the obvious: “But they’re real nudists.”

��

Chris is Christopher McCandless, the 22-year-old from Annandale, Virginia, who graduated from Atlanta’s Emory University in 1990, donated the remaining $24,000 in his college fund to Oxfam America, cut ties to his parents, and took off on a quest to escape his privileged upbringing. For two years, he wandered North America alone as “Alexander Supertramp,” abandoning his car in the Arizona desert and then riding trains and hitchhiking from California to South Dakota to Oregon to Utah to Washington to Baja and points in between. Then, in the spring of 1992, he walked into the Alaskan wilderness for his final adventure. Four months later, trapped by a swollen river that had cut him off from civilization, he starved to death in an abandoned Fairbanks city bus.

After detailing McCandless’s tragic odyssey in the January 1993 issue of ���ϳԹ���, Jon Krakauer expanded the story into 1996’s Into the Wild. The book spent 103 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and is now taught in English classes all over the country, a sort of nonfiction Catcher in the Rye that takes on the same issues of family dysfunction, misguided youth, wanderlust, and the pitfalls of an unexamined life. At its heart, it is also a classic adventure story. Over the years, hundreds of readers have been moved to write to the McCandless family; others have dropped everything and made pilgrimages to visit the places Chris traveled, including the remote Alaskan bus where he died.

Filmmakers have been equally gripped by the book, none more than director and Academy Award-winning actor Sean Penn, who’s spent the past ten years trying to make a movie out of Into the Wild. “The story just touched a chord,” says Penn, describing his discovery of the book back in 1996. “One part was trust issues in a family and society at large, but the greater aspect was this wanderlust that everybody shares in.”

In the fall of 2005, Krakauer and the McCandless family finally signed off on Penn’s plans for a movie (the film hits theaters September 21), in part because of his pledge to stick so closely to the true story. The next spring, Penn hit the road with an all-star cast and crew—including actors Emile Hirsch, Vince Vaughn, Catherine Keener, William Hurt, and Marcia Gay Harden and Brokeback Mountain executive producer William Pohlad. For six months, the 150-member team has crisscrossed the country, shooting at 36 locations McCandless had visited. Penn was fanatical about the details. Everything has been exhaustively accurate, from the facial hair of the star (22-year-old Hirsch plays McCandless) to the make and model of the Alaskan bus to, yes, the presence of real nudists on the set.

Today is the 78th day of shooting. Penn, wearing jeans, a light-green T-shirt, work boots, and a straw cowboy hat, is blocking out a few movements with Hirsch for the next scene. McCandless will get dropped off at his wilderness campsite by Ronald Franz (played by veteran character actor Hal Holbrook), an 80-year-old Army veteran from nearby Salton City who befriended McCandless and eventually offered to adopt him.

“Let’s use the ‘shut the fuck up’ rule,” says Penn, to no one in particular. The crew goes silent and we watch as the scene unfolds.

Action!

Franz’s Ford Bronco approaches the spare campsite and the two get out. McCandless sits on the hood of the truck—just as Penn had blocked it out—and explains to Franz his philosophy on getting a job. “I think careers are a 20th-century invention,” he says. He’s wearing a red T-shirt, short blue running shorts, and New Balance running shoes. “I’ve got a college education. I’m not destitute. I’m living like this by choice.”

“In the dirt?” asks Franz, looking at the small green tarp McCandless has tied between two creosote bushes for shelter. “Where’s your family?”

“I don’t have a family anymore,” says McCandless.

In fact, McCandless’s parents, Walt and Billie, and his younger sister, Carine, are all here on the set today. Carine is standing a few feet away and watches the scene play out for three more takes. This convergence of reality and fiction is both startling and heartbreaking. But then, how Penn, this crew, and the surviving family all banded together to tell McCandless’s story is an unbelievable tale itself. Here, from the beginning, they reveal it in their own words.

Like many people who worked on the movie, Sean Penn remembers exactly when he first discovered Into the Wild.

SEAN PENN, 47, screenwriter and director: In 1996 I walked into an open-air bookstore in Brentwood and I saw the book. Well, really I saw the bus on the cover, and I don’t know why, but it intrigued me. I picked it up and took it home. By morning I had read it twice and wanted to make a movie out of it. That was the first thought I had. I called Jon Krakauer, and he told me that he had an agreement that any discussions of a movie would involve the family before he did anything with the rights. Initially I found myself competing with a bunch of people who had gotten there before me.

��

BILLIE McCANDLESS, 62, Chris’s mother: We were immediately inundated with producers and directors from everywhere. We sent everyone through our attorney first. Eventually we narrowed the list of people to five and called some meetings.

WALT McCANDLESS, 71, Chris’s father: Most of the people just struck out. One group said, “We’re gonna change the story and have Carine go look for Chris.” And that was instant death.

CARINE McCANDLESS, 36, Chris’s sister: People tried to impress us with power and big names. But it wasn’t about money. Sean Penn was clearly from the beginning someone who was more interested in a true accounting than in what would sell the most tickets.

BILLIE: Walt designed a little rating chart which we all filled out individually as we met with people. It turned out that all of us picked Sean Penn. It was just everybody’s gut feeling.

PENN: I made a couple trips to see the family. And then when I was on my way to the airport to make what would have been my final trip, Billie had a dream that her son didn’t want a movie made. I told her that if I didn’t respect dreams, then I wouldn’t be making movies. And we pretty much left it at that. That was nine years ago.

WILLIAM POHLAD, 51, producer: Sean kept in touch with the family and maintained a line of communication. He said he respected their decision but, if they ever changed their minds, he would still be interested.

CARINE: Sean politely kept his foot in the door for ten years. That’s the best way I can put it.

PENN: I think we exchanged a few Christmas cards over the years. I had never given up on it. I believed that at some point or another they would make a decision to do it.

BILLIE: [In 2005], Jon found out that things were heating up again. Somebody, not Sean, was planning to do the movie anyway, without the family or Jon’s participation. If we ever did want to do something, now was the time.

CARINE: Sean came out to my house in Virginia. Jon and my parents were there, and we all knew we were gonna make a final decision after that meeting. I have a big backyard, and we sat outside for a while. We made dinner together. It was a chance to ask all the hard questions.

WALT: Sean said, “I will devote two years of my life to this and not take on any other projects.” And he did.

PENN: I wrote a new draft very fast once the time came. Usually you write something and it takes a year to get the financing. With this case, it was a couple of weeks and we were starting to talk about start dates.

With backing from Pohlad and Paramount Vantage in place by February 2006, Penn had just a few months to assemble a team and scout locations before shooting began that spring.

PENN: It took cumulative forces of will to make this happen. I was able to put together a sensational crew. It was like I put a call in to Special Forces for an emergency mission and everybody just went for it.

FRANK HILDEBRAND, 55, executive producer: Sean started by retracing Chris’s steps and tried to hook up with as many of the real people who knew Chris as possible. One of the key characters, Wayne Westerberg, was a driver on the film.

WAYNE WESTERBERG, friend and former boss of Chris McCandless who hired him to do odd jobs at his grain elevators in Carthage, South Dakota (Westerberg, who identified McCandless’s body in Alaska, still refers to his friend as “Alex”): My phone rang in the truck and it was Sean Penn. He wanted to come basically the next day to South Dakota. He asked me to come work on the movie, and I thought, What other time in my life would I be able to work on a production for a year? So I parked my truck and put everything on autopilot and ended up going with those guys last year. I worked in transportation.

Of all the locations Penn had to scout, the remote spot in Alaska where McCandless spent his final months proved to be the most difficult to replicate. He started by visiting the real bus, which still sits in the wilderness west of Healy.

PENN: We went in the winter on snow machines. [The bus was] in exactly the same state. The most impacting thing is that [McCandless’s] boots are still sitting there on the floor and his pants are still there folded, with the patches he sewed into them. As a story that I’d followed for so long, that was a pretty big moment… It was very moving, but I was also there to work. I knew I wasn’t going to shoot there. It would have been obnoxious, a kind of rape of the area to have a whole crew there. I was going there to make a pilgrimage but also to find a reference. It affirmed for me that what I had in my head was quite accurate. Our place is an approximation.

We had a scout by the name of John Jabaley—he was the point man to find our location. We searched for over a month. It was a ton of time walking in the snow and trudging and getting cold and wet and frustrated. I was getting to the point where I was wanting to take it out on John, because we hadn’t found what I wanted. But that night he came and said, “I think I might have found it.” So we took snowmobiles, and as we approached I could see that this is what I’d had in mind. The hill from the river was dead on. And just as we got to the top, where we eventually placed our bus, there were three moose. And I just said, “This is it.”

WESTERBERG: The real bus was a 1942 International. Those had so much iron in them that if they were in the States they’d already have been scrapped. But it costs so much to haul one in Alaska that it’s cheaper to let it rot in a field. And sure enough, we found two of them up there.

Originally, Penn wanted to cast unknown actors in the film. But with so little time to prepare, he chose veterans such as Vince Vaughn and William Hurt—people “who weren’t gonna need a lot of nurturing.” The toughest decision was casting the part of Christopher McCandless.

PENN: I’d seen Lords of Dogtown and thought Emile Hirsch’s performance was intriguing. So I spent four months of on-again, off-again meetings with him to try to get a sense of whether he was gonna be ready to make the kind of commitment that was necessary for this. This was gonna be a brutal kind of thing. I had no idea how he would blow our minds.

EMILE HIRSCH, 22, actor: Sean said, “I’ve got this book and I want you to read it.” I’d seen a segment [about McCandless] on 20/20 when I was nine, and it made a big impression on me. The idea that a person would go off and be alone and have to suffer and have joy alone is something that to a kid is almost impossible to understand. And that was the reason I never forgot it. So I read the book the next day and flipped for it. There’s this wanderlust, this unexplored side; everyone wants to go out on the road and have an adventure, you know? I was 21. My life had been kind of flat and uneventful at the time. The book just kind of reawakened what was possible. It was like On the Road without all the Benzedrine.

WESTERBERG: I got to know Alex pretty good. [Emile] was a lot like him, same size and build and came from growing up with money and found some adventure in this. He tried to get totally involved in it.

WALT: You see Emile up close and he doesn’t look a lot like Chris or have the same voice sound. That’s an almost impossible thing. But you see him in the action parts of the film, when he’s walking into the wild after they let him off at the trailhead, and, boy, he looks exactly like him.

In order to capture scenes in the snow, filming began in Alaska on April 15, 2006. The crew would eventually make four trips there, trying to depict each season McCandless experienced. In between, they shot at 35 other locations in the U.S. and Mexico. The quest for authenticity led to some risky moments, especially for Hirsch.

PENN: For the winter scenes, the snow made it easier. The bus location was at the end of a paved road, then three miles of dirt road and then another mile snowmobile in. Then we had to cross a river. It was rough terrain, and sometimes when we finished shooting it was pitch black. We had our fair share of accidents, but no one got hurt.

POHLAD: Yeah, it was a nightmare. Where we ended up was a major undertaking. Then you would have thought it would have gotten better [after the snow melted], but it was worse.

PENN: When we went back in May to do the second shoot, the river was totally uncrossable and snowmobiles weren’t really an option anymore. We had to build a crude bridge. Finally, the fourth time we went back, the river was so high it was threatening the bridge. That got exciting. [We] cut a tributary, and that helped ease the pressure a little. But every day we were just sort of giggling and hoping.

HIRSCH: In the very beginning, we shot the scene where McCandless gets dropped off in Alaska by Jim Gallien. Sean used the real Jim Gallien in the movie. Jim had a gold watch that McCandless had given him, and he said to me, “I think you should have it.” And I wore the gold watch the whole time on the adventure. I felt like it kind of protected me. I was in situations constantly where I could get seriously hurt—if not die—if I lost concentration.

PENN: It was a constant worry. Every day was one hand held out protectively and the other crossing its fingers. Emile is a phenomenon of balance, though, and you see it on film with things that weren’t rehearsed.

HIRSCH: It was such a big adventure. You know, jumping off a cliff into the Colorado River one day with Sean yelling “Action!” behind me, to running with wild horses, to kayaking through rapids in the Grand Canyon, to climbing up steep, snowy mountains in Alaska and worrying that I’d roll 200 feet down this hill, to a grizzly bear walking right up to me for a shot and doing it 12 times, to being in South Dakota and driving a tractor, to walking around Skid Row in L.A. with all the junkies trying to get money from me. I saw this slice of America that was unforgettable.

In Arizona, Penn wanted to film scenes of Hirsch kayaking on the Colorado River. McCandless had once canoed nearly 400 miles of the Colorado to the Gulf of California.

HIRSCH: I’d never done any kayaking. I had one day of practice, and then on the day of the scene, on our jet boat, we went right by the rapids where I’d practiced. I thought that was where we were shooting, so I said, “Why are we driving by it?” Sean looks at me and says, “That’s not a rapid.” And we go a couple miles down, and there’s this huge, bone-crushing rapid that made the one I’d already done look like a tide pool. And Sean, being a man’s man, said, “I’ll go first,” and he hadn’t even kayaked before. He went two-thirds of the way down and just ate shit.

PENN: The only thing I could offer back [to Emile] was to be wherever he was and do the same thing he was doing. Not as well, by the way.

POHLAD: [As a producer] you’re always nervous about all of it. Sean too, because he’s right beside him. He never wanted to be seen as the guy taking a backseat for anything.

If the shooting in Alaska and on the Colorado required physical toughness, capturing much of the family history demanded emotional strength. For McCandless’s parents and sister, it meant dredging up some old ghosts. The movie includes a violent argument between his mother and father, as well as the father-son tension over careers and money that led, in part, to Chris’s decision to leave in the first place.

HILDEBRAND: Sean made a point of getting them to sign off on the script. Carine was involved in writing the voice-over that Jenna Malone reads through much of the movie.

CARINE: If there was something I wasn’t comfortable with, Sean was open to my suggestions. He knew how to take our concerns for Chris and make that come through in the film.

POHLAD: As Sean spent more time with the family, I think the story started to open up even more. That caused some controversy. The parents had some ups and downs and nervousness. But Sean handled it all very well.

PENN: There were difficult points. It was tender ground to cross. It was the most treacherous with the parents. We had some serious discussions. Sometimes they were pretty heated. But my first obligation was to Chris. And every time, within a couple of days they would come to an understanding. That takes fucking courage to give in to it like that. And they did it.

WALT: It was hard—harder than each of us thought it would be.

BILLIE: We feel blessed that this was open to us. I thought it was just laid in the cards whether it was going to be a good or bad experience. But we do think it was handled with a lot of respect. We are at peace with what Sean did. Everyone talks about Sean being Hollywood’s bad boy. Sean Penn is a gentleman.

The most challenging part of the whole shoot was filming McCandless’s final days of starvation in Alaska.

HIRSCH: Everyone pretty much left me alone. So a lot of those scenes are me deciding what to do in that moment as though I was really living out there. I’d be cold and freezing and hungry. But the discomfort and the harshness helped me relate to what Chris had gone through. I lost 41 pounds. I’m five foot six. I went from 156 pounds to 115 pounds. They gave me a couple weeks off. I had to gear up to do it, you know? [I’d do] two hours of cardio a day on very few calories. I had teeny bits of food every day. I went to a level of hunger I had no idea existed. We shot for two weeks like that.

HILDEBRAND: Towards the end it was torture for Emile. He was really emaciated. We shot his death [in August], and it was 12 hours from the time McCandless died. It just happened that way.

Among those involved with the picture, expectations are high, and many people feel changed by the experience.

WESTERBERG: [Sometimes I think] if I hadn’t identified his body in Alaska, he probably would have been buried a John Doe. And then there never would have been any of this. It’s really strange. A lot of time has passed. There’s been so much publicity, and I think it changes the whole concept of grief. I’ve just gotten… immune to the whole thing.

PENN: I do have hopes of what people are gonna take away from this movie, but not because I’m going to reveal those hopes in an article. I think it’s there. I will say this: I hope people get out of the movie what I got out of reading the story the first time I came across it.

CARINE: Being on the set was kind of comical; it was like this big machine. I could hear Chris in my head saying, “This is just nuts.” But I didn’t really care about the behind-the-scenes. When we worked on the final edits of the narrative, that’s what my focus was on. Those are my words about my brother. It’s about Chris, but he’s not here to speak. The last version I saw, I had about 100 pounds come off my shoulders.

BILLIE: Chris did not understand or agree with the way the world was going, and he wanted to change it. He wanted to change it since the beginning of high school.

WALT: He wanted to change it as a little boy.

BILLIE: He also understood that to change things you needed to understand them. And he wanted to learn about life from the ground up. And that was what he set out to do. And unfortunately he didn’t make it. But I don’t know—look at all that’s happened because of him. I want this movie to do what the book did: grip people in the heart. Make people think. Bring people and families together. It’s a lesson.