BIOLOGIST AND LEGENDARY ultramarathoner Bernd Heinrich is comfortable with extreme athletic adversity. “You can’t experience the light until you know what the darkness is about,” says the author of Racing the Antelope: What Animals Can Teach Us About Running and Life. “You can’t experience the joy and freedom of running without knowing the other side.”

HEAD STRONG: Mental excercises are the key to rushing negativity and unlocking your athletic potential.

HEAD STRONG: Mental excercises are the key to rushing negativity and unlocking your athletic potential.

What lurks on the other side? Anxiety, fear, pain, and fatigue: the dark counterparts to an athlete’s assets and guardian angels. Like the rest of us, Heinrich doesn’t exactly enjoy these bedevilments, but he knows them intimately, given his studies of animal and human endurance at the University of California at Berkeley and his own successful pursuit of a masters ultramarathon world record. And yet Heinrich still confronts the reality that some runs are fast and strong, others strained and painful, even under seemingly identical conditions. Lucky for us, research is beginning to shed some light on that mystery. The physiology and psychology of crippling sensations like anxiety, fear, pain, and fatigue have gotten clearer over the last ten years as advances in scanning the brain’s electrical activity have allowed neuropsychologists to start mapping the connection between body and mind. Sports shrinks, coaches, trainers, and professional athletes have seized upon those findings—and they’ve discovered what the rest of us have suspected all along: that our emotions and sensations have heft, especially when it comes to performance.

While less tangible than, say, frostbite, emotional distress sets off a chain reaction of physical consequences in the body, triggering (or restricting) hormonal secretions that drive heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration. They can mobilize the body to tap its energy reserves faster, or crimp the fuel lines and cause a midrace crash. These processes interact with each other intricately, especially in the evolutionary proving ground of intense exertion. Fear can temporarily trump pain; elation can counter fatigue; exhaustion can magnify hurt. Whether you’re conquering your first lead climb or training for an adventure race, understanding these interactions is as important as logging miles on the road or hours in the gym. It’s a head trip you can’t afford to go without.

The Battle of the Butterflies

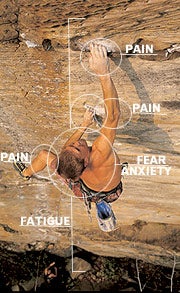

Fear & Anxiety

FEAR IS SUDDEN AND ARRESTING, a blind-side Holyfield punch. It can start with a sloppy foothold, a hooked ski edge, or an ill-timed paddle stroke. As your body veers toward trouble—cliff, tree, Class V hole the size of a Winnebago—neurons relay electrical impulses from your eyes to your brain’s gumball-size amygdala, which sounds the alarm to the hypothalamus. The two structures begin gushing hormones, urging the adrenal glands to start pumping epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol, three stress hormones that ramp up glucose production, increase heart rate, speed up your breathing, and often leave you sweating like a goose at a down-jacket factory. On the upside, though, fear is turbocharging muscles and the brain for confrontation or evasive action—the classic fight-or-flight response—and that can help performance.

Anxiety is a more plodding matter, says Mary Meagher, a psychologist in the behavioral neuroscience group at Texas A&M University, and it’s a reaction that’s more troublesome to athletes. “Fear and anxiety have different underlying brain circuitry,” she says. “Anxiety is future-oriented; it’s about potential threats. You’re uncertain, aroused at a low level, with clenched muscles and increased pain sensitivity.” This is what you might experience before a race or competition, or perhaps when you realize you’re 30 feet from the top of your climb and you just placed your last piece of gear (see below for advice on overcoming such predicaments). Anxiety stimulates the amygdala, triggering the production of cortisol but generating less heart-whumping adrenaline than fear does. Fear inspires alarm and action, often suddenly and acutely, outstripping thought; anxiety unfolds more slowly, disrupting thought and evaluation. Thus anxiety is more insidious, magnifying injuries, hindering movements, and knocking athletes out of the blessed neural harmony of competitive flow. But it’s more easily controlled than fear.

- THINK POSITIVE. You’ve heard it before, but studies by Meagher and others have shown just how well positive thinking can reduce anxiety’s physical effects. The trick is to pick realistic motivators, says Steven Ungerleider, author of Mental Training for Peak Performance. “You can continually remind yourself,’I’ve done this, it’s safe—it’s dark, but I know this trail.'”

- MENTALLY PRACTICE OVERCOMING ADVERSITY. Imagine yourself in tough situations. Then decipher what specifically primes your anxiety pump—and what affirmations dull that response. Focus on controlling your breathing (slow and deep, not rapid and shallow), on staying in the present moment (you’re on the rock, not plummeting from it), and on visualizing success (you’re pulling fluidly through the move).

- DEVELOP A RELAXATION RITUAL. A simple exercise consistently performed before workouts and events can fend off anxiety. Try this: Lie down comfortably and then progressively tense and relax your major muscle groups individually, starting with your right calf.

Running Past Empty

Fatigue

COMPARED WITH FEAR AND ANXIETY trip wears on—and on—gradually depleting your energy stores. You feel sluggish, loopy, maybe even disoriented. Crank up the intensity by climbing a big hill, and you expend the dregs of your stored energy, causing blood sugar to plummet and your muscles to lock down. Now you feel lousy, maybe even panicky, depending on the pickle you’ve gotten yourself into.

The body uses different fuels for different levels and durations of exertion—running a half-marathon (moderate duration, moderate intensity), for example, mainly taps the glycogen stored in the muscles and liver, while a 25-mile hike (long duration, low intensity) would deplete those stores and start burning fat for energy. Sprinting from a chargin’ grizzly sow, on the other hand, would tap anaerobic systems to combust the tiny amount of energy stored inside the muscle cells. Understanding these processes can help you manage energy output, but fuel burning isn’t entirely mechanical. “I started off focusing on muscles, like most exercise physiologists,” says J. Mark Davis, director of the University of South Carolina’s exercise biochemistry laboratory. “But they didn’t tell the whole story.” Instead, Davis found himself drawn to the brain’s role in fatigue.

During endurance events, depleted energy stores can wreak havoc on your mental state. As fatigue sets in you’ll lose concentration (increasing your chances of injury) and become susceptible to negative thoughts (worrying about your condition and focusing on the distance left to travel). Because mood can drive metabolism, the more stressed out you are, the higher your metabolic rate, causing your body to vaporize fuel even faster. Fortunately, athletes who learn to recognize the emotional results of fatigue can address mood swings with simple mind exercises. Focusing on breath to stay present in the moment, say, or mentally breaking down long distances into more manageable segments, can damp the mental—and therefore physical—effects of fatigue.

Mental games have their limits, of course. If you haven’t conditioned your heart and lungs to move more blood and oxygen or built glycogen reserves through endurance training and ample rest (see tips below), you can forget thinking your way to a first-place finish. But by feeding the mind with a combination of nutrition, training, and mental exercise, you’ll be on your way to optimal performance. “The impulses come from the brain,” Davis says. “When it’s not working well, the flesh doesn’t work well.”

- DRINK PLENTY. Quaffing eight to 12 ounces of sports drink every 15 minutes from the start of a 90-minute-plus workout will divert (or at least delay) fatigue’s hormonal tidal wave. “Stay ahead,” Davis says. “You can’t catch up when you’re a liter down.”

- HOP ON THE LONG, SLOW TRAIN. Don’t neglect “overdistance” training (workouts at mileage longer than your race). Hour-plus sessions at 60 to 70 percent of your max heart rate condition your body to burn fat more efficiently and go longer before tiring.

- CONSIDER CAFFEINE. Java- or green tea-fueled training isn’t for everyone, but Davis says moderate caffeine intake (16 ounces of coffee or the equivalent) may fend off fatigue during long outings.

- EXERCISE YOUR BRAIN. Fight fatigue the same way you combat anxiety. During distance training, develop mental exercises (again, focusing on your breath or breaking down long distances) that help you maintain a positive mood even when fatigue sets in.

The Agony of Success

Pain

“PAIN SIGNALS DON’T have a straight shot to the brain,” says Wendy Sternberg, a biological psychologist at Haverford College who studies how competition affects the perception of pain. “That allows for modifications. The brain determines how much influence pain-transmission neurons have.”

Here’s how it works: Tiny monitors called nociceptors that share space with sensory neurons detect damage—like where your wrinkled sock is flaying the ball of your foot—and sound the alarm, sending signals to the dorsal horn of the spinal column. That structure, sort of an Internet router of hurt, sends more messages to a variety of sites in the brain, which interpret the source and extent of the pain, and transmit the appropriate sensations. The essential point here is that the spinal center’s communication with the brain is two-way. And in special circumstances—the heat of competition or moments of intense danger—the brain can dull the signals it sends.

Pain experts call this stress-induced analgesia—an evolutionary perk. “If you need to escape a lion, it lets you sprint on a broken leg,” says Sternberg. This scenario has little bearing for athletes, but recent probes into the phenomenon do. The lactic acid of a halfhearted practice sprint, Sternberg believes, burns hotter than the pain of more meaningful competition. Sternberg tested this by zapping athletes’ fingertips with a heat-emitting light and by dunking their arms in ice water; subjects withstood pain longer right after competition, compared with two days before and two days after.

The trick is to acknowledge and accept the pain (or “associate” with it, in the sports-psych jargon) rather than trying to distract yourself from it by silently reciting poetry or multiplication tables; befriending the torment helps the brain cool the pain circuitry. Rather than anxiously focusing on the blast furnace melting your quadriceps, imagine the pain as something positive, an inevitable but transient part of pursuing athletic passion (see “Reframing the Hurt,” below). “I think of feeling bad as money in the bank,” says Bernd Heinrich. “It stokes up my fire to run. When I finally feel good, I revel in it.”

- REFRAME THE HURT. View pain as a necessary part of athletic success and pleasure as an essential part of managing pain. John Eliot, director of performance enhancement at Rice University, suggests developing almost talismanic images of what you love about your sport—topping out on your climb, crossing the finish line, a big, wet congratulations kiss from your crush—and summon them when you’re hurting.

- BELLY BREATHE. Fast, shallow breaths can increase tension and pain. Deep belly breathing can help kill side-stitch cramps, and its ability to release tension and flood the tissues with oxygen can soothe other hurts as well. Try this: Breathe as deeply as practical, pushing your diaphragm out as you inhale, sucking in your gut when you exhale.

- GRIT YOUR TEETH AND GRIN. Smiles, and especially laughter, even when not entirely sincere, have been shown to trigger the brain’s “happiness centers” and reduce cortisol levels. This can boost your mood and dull pain. Or at least it’ll psych out rivals.

- EXTEND YOUR LACTATE THRESHOLD . The leg burn is as much a part of running a marathon as the logo-bedecked finisher’s T-shirt. But it can be delayed (the burn, not, alas, the shirt) with interval training; in your workout, add three to seven bursts of effort that push you to your lactate threshold (80 to 90 percent of maximum heart rate).