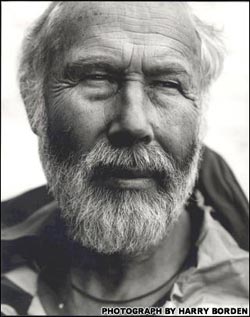

One of climbing’s most famous survival sagas began on the night of July 13, 1977, after British mountaineers CHRISTIAN BONINGTON and Doug Scott completed the first ascent of Pakistan’s 23,900-foot Baintha Brakk—a beastly massif known as The Ogre. During his rappel down, Scott swung wildly across the face and broke both legs. Bonington later fractured several ribs, and when the climbers stumbled back to base camp, with Scott crawling the entire way, they found that their support team had left. Their rescue took ten days, and 24 years and 25 failed attempts passed before anyone summited The Ogre again. Bonington, now 68, still leads alpine expeditions.

CLICK HERE to hear Bonington’s tale of survival To hear the this audio clip you will need the latest version of

CLICK HERE to hear Bonington’s tale of survival To hear the this audio clip you will need the latest version of

In an interview this past summer with ���ϳԹ���‘s Tim Neville, Bonington recounted the glorious moments on the peak before Scott’s accident, the agonizing, handicapped descent, and the wrenching days in waiting for rescuers atop the roof of his porter’s home—confessing that, beneath the suffering, there’s a strange exhilaration to surviving the painful and difficult. For an edited audio clip of the interview,

1980: The Mountain Blows its Top

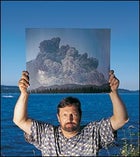

Keith Ronnholm at Lake Washington in Seattle, July 16, 2002.

Keith Ronnholm at Lake Washington in Seattle, July 16, 2002.Mount St. Helens erupted on the morning of May 18, 1980, killing 57 people and causing $1.1 billion in damage. KEITH RONNHOLM, then a 28-year-old graduate student in geophysics at the University of Washington, was camping at Bear Meadow that day, ten miles northeast of the volcano. He escaped in his car, but not before shooting a set of famous photos that ran on the cover of Nature. “About 8:30, I looked at Mount St. Helens and saw the entire north side flowing, sliding down. Within 15 seconds the eruption cloud was a mile high and a mile wide. The cloud hit a ridge in front of me and swirled up and over it like a wave hitting a breakwater. At one point, I was literally under a mushroom cloud, with lightning bolts coming out of its stem. These days, whenever I go somewhere, I look at how I can escape. It’s not that I’m paranoid. But I have an awareness that the earth is not steady—that we’re tiny creatures who are very susceptible to nature’s whims.”

Interview by Fen Montaigne

1984: The Sky Is Falling

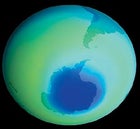

Ozone hole image recorded by NASA’s Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer, October 1985.

Ozone hole image recorded by NASA’s Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer, October 1985.In late 1984, British atmospheric scientist BRIAN GARDINER and two colleagues, Joseph Farman and Jonathan Shanklin, stunned the world with their discovery of a hole—roughly the size of Australia—in the protective ozone layer over Antarctica. Scientists quickly fingered the culprit—industrial gases called chlorofluorocarbons—and within two years, most nations had agreed to ban the gases outright. Gardiner, 57, now leads the British Antarctic Survey’s Ozone Monitoring Program in Cambridge, England. “When this thing happened, it was a wake-up call, a shocker. But we learned from it. First, that we need to work harder at understanding the atmosphere we breathe. Second, that we need to realize how mankind’s activities can cause unpredicted and quite dramatic changes. Detecting the ozone hole was, really, a lucky break, because that problem was relatively easy to solve. The ozone hole should begin to get better soon. We could see some improvement in the next five or ten years. But when you’re talking about the greenhouse effect and climate change, that pervades all aspects of industrial and economic life throughout the world. I’m an old guy now, a dyed-in-the-wool curmudgeon. But I guess I’m saying the most radical thing: I’d like to see us convert worldwide from fossil fuels to solar, wind, wave, biomass, and so on. Let’s not wait to find out what we shouldn’t be doing. We’re playing dice with our future.”

Interview by Rob Buchanan

1985: Pop Go the Summits

Dick Bass at Snowbird, Utah, July 24, 2002.

Dick Bass at Snowbird, Utah, July 24, 2002.On April 30, 1985, with help from guide and filmmaker David Breashears, Texas millionaire DICK BASS topped out on Mount Everest, becoming the first person to climb the highest peak on each of the seven continents—Everest (Asia), Mount Elbrus (Europe), Aconcagua (South America), Mount McKinley (North America), Vinson Massif (Antarctica), Kilimanjaro (Africa), and Mount Kosciusko (Australia). The 72-year-old Bass, who founded and owns Utah’s Snowbird ski resort, hopes to climb Everest again in 2003, during the 50th anniversary year of Sir Edmund Hillary’s first ascent. “At first, the professional climbers were pissed. They resented some 55-year-old yahoo from Texas climbing these mountains that they’d spent their lives dreaming about. There was a lot of talk about how I ‘bought the mountain.’ Well, bullshit. I failed three times on Everest before I made it. Dave and I climbed that thing like any two climbers going out together—just the two of us, with our Sherpa, and without fixed ropes. When I see guides now, they hug me, because the Seven Summits made the mountain-guiding profession. It made them! Some 100 people have done the summits by now—they’re the equivalent of earning a super Boy Scout merit badge.”

Interview by Bruce Barcott

1990: The Word Gets Out: Maverick’s

Flea Virostko takes on a 50-footer at Maverick’s, November 21, 2001.

Flea Virostko takes on a 50-footer at Maverick’s, November 21, 2001.Maverick’s, the monster wave 22 miles south of San Francisco, gained notoriety in the early nineties after a contingent of surfing’s top guns took on its 35- to 50-foot faces, culminating in the 1994 drowning death of big-wave legend Mark Foo. But before 1990, Maverick’s had been the private playground of local surfer Jeff Clark. On January 22 of that year, Clark convinced Santa Cruz surfers Tom Powers and DAVE SCHMIDT to join him as a powerful Aleutian swell rolled in to the Northern California coast. Schmidt, now 44, spread the word, and the world was in on a dangerous secret. “Tom and I were standing at Ocean Beach watching these 15- to 20-foot storm sets rolling in. I was thinking: I’m not going out. Then Jeff pops up and says, ‘Hey, I’ve got a place with a perfect left and right break, right through a channel.’ So we go down there, and I look south to the break and see this big A-frame peak 20 feet tall. I was in shock. I went out, got up, and the wave was like an elevator—it just jacked me up and up and up before finally releasing me. After six rides, I got in, kissed the beach, and said, ‘What is this place?’ Even now, when I talk about it, my hands start sweating. You’re pretty much cheating death at Maverick’s. It’s the only wave I know that registers on the Richter scale.”

Interview by Daniel Duane

1993: Lynn Hill Busts a Move

Lynn Hill in Moab, Utah, July 13, 2002.

Lynn Hill in Moab, Utah, July 13, 2002.The Nose route on Yosemite’s El Capitan is a famously difficult 34-pitch climb up 2,900 feet of steep and fissured granite, and only one person has done it without mechanical aids: LYNN HILL Now 41, Hill completed her epochal free-climb over four days in September 1993, after retiring from a dominant World Cup sport-climbing career. A year later, she freed The Nose again—this time in less than 24 hours. ” I went to Yosemite after I got tired of competing. I thought: I’m going to take all the things I’ve learned and apply them to something big. I climbed The Nose as a kind of performance art, because I wanted to show the power of having an open spirit. I felt so strongly about this climb that it’s no surprise it seeped into my dreams. When a climb gets difficult and you’re not sure you can do it, the only thing you’ve got is your will to persevere. That toughness and faith are priceless.”

Interview by Jason Daley

1995: Look Who’s Back

A wolf in Yellowstone National Park.

A wolf in Yellowstone National Park.The last native gray wolf died in Yellowstone National Park in the mid-thirties, the victim of a U.S. government eradication campaign that relied on everything from poison and traps to the stomping of wolf-pup litters. Fast-forward through six decades of slow enlightenment, to March 21, 1995. Despite a series of intimidating legal challenges, 43-year-old MIKE PHILLIPS—wildlife ecologist and Yellowstone Wolf Project leader—was preparing to reintroduce Canis lupus to Yellowstone. Two groups, captured in Alberta, Canada, had been placed in remote chain-link enclosures inside the park. After ten weeks, they were showing encouraging signs of acclimation. “Under enormous scrutiny, we had opened the gates . . . and nothing happened. Jokes circulated about the ‘welfare wolves’ that were content to lie around and be supplied with elk carcasses. Total bullshit. They just needed to do this on their own time. We were on our way to check the Rose Creek pen, where there were three wolves: a big, assertive alpha male, No. 10, his mate, No. 9, and her daughter, No. 7. Just as my field biologist, Douglas Smith, and I set off, a blizzard hit—we could hardly see our path through the trees. And then a wolf howled behind us. We turned, and there was No. 10, just visible through the snow, huge and free, the first wild wolf released into Yellowstone. We bailed out of there, but No. 10 followed us at a distance, howling frequently. He was just letting us know that this was his territory.”

Interview by Jonathan Hanson

1996: All Eyes on Top of the World

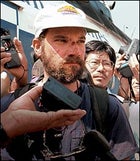

Jon Krakauer speaking to reporters in Kathmandu, Nepal, May 16, 1996.

Jon Krakauer speaking to reporters in Kathmandu, Nepal, May 16, 1996.The 1996 tragedy on Everest, in which eight climbers were killed by a brief but brutal May snowstorm, was at once the most famous and most infamous mountaineering story of the century—an event that captured the public imagination even more than the first Everest ascent in 1953. Climbers routinely and stoically die faint, distant deaths. But this time around, staid network anchors, the front page of The New York Times, your neighbor who had never been outdoors—everybody had something to say about it.

This happened in part thanks to media serendipity. World-shrinking advances in communication technology had just coalesced: the Web, cell and sat phones, online journalism. At the same time, despite a wired world, there was the nearly unbearable suspense of a temporary news vacuum at the height of the storm. Then came reports of the numb, dying throes of veteran mountain guide Rob Hall. Exhausted and frozen near the summit, he was patched through via radio to his pregnant wife in New Zealand to say good-bye forever.

���ϳԹ��� editor-at-large Jon Krakauer—who climbed in Hall’s group, and who barely survived Everest himself—first told his story in this magazine, in a riveting account that he later expanded into his international bestseller Into Thin Air. It wasn’t just the story’s pathos and finality that captured the world, but the Shakespearean drama of it all. The mortal mistakes on a mythic mountain, the ambition and hubris, the flawed heroes. Like all great drama, Everest ’96 was, at heart, a morality play. Is it right to pay someone to drag you up Everest when you have no idea what you’re doing? For that matter, is it right for anyone—someone’s father or sister, mother or brother—to willfully attempt a mountain well-known for its deadly maliciousness? Who’s responsible for whom? For a long interval, in the midst of peace and great plenty, the Everest disaster sparked heated, wonder-struck debates over the ethics of risk in late-20th-century American life.

And the moral? Despite humankind’s inventiveness and transcendent boldness, nature remains unpredictable, unaccountable, and unconquerable.—Mark Jenkins

1999: The Balloonatics Blast Off

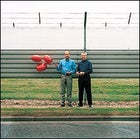

Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones at Heathrow Airport, London, July 25, 2002.

Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones at Heathrow Airport, London, July 25, 2002.On March 21, 1999, BERTRAND PICCARD of Switzerland, 44, and BRIAN JONES of England, 55, circumnavigated the globe in a $2 million, 9.3-ton hot-air balloon, beating out five other teams vying to circle the earth first. Flying as high as 36,000 feet in the Breitling Orbiter 3, Piccard and Jones navigated 28,431 miles in 19 days, 21 hours, and 55 minutes, touching down on a plateau in the Egyptian desert. “Jones: I agree with those who suggest this was probably the greatest flight ever made within the earth’s atmosphere. Consider: It was 216 years between the first manned balloon flight and our round-the-world success. It was 66 years between the flight of the Wright Flyer and the Apollo 11 moon landing.

PICCARD: Sometimes I still can’t believe we made it. It’s nice to hear people compare our achievement with milestones like Hillary’s climb of Everest, Lindbergh’s crossing of the Atlantic, or the first polar exploration.

JONES: Explorers are continuing to find new species of flora and fauna in the jungles, and creatures in the sea. There are more mountains out there that have never been climbed than ones that have. I reckon we’ve only just scratched the surface of exploration in our world.”

Interview by Mike McQuaide