For our second annual Zero to Hero special, six ���ϳԹ���rs dug deep and pushed through fear, puppyhood, and fists of fury to find their inner resolve—and show you how to evolve.

Deep Thoughts During PADI Certification

It was the turtles that changed me. Green sea turtles, four feet long, 400 pounds, gliding through the saline solution 25 feet below the surface like chubby, hard-shelled aliens.

I'd come to Hawaii to become a PADI-certified Open Water Diver, with two days of pool-and-ocean-based instruction. The week before, in my living room, I'd completed PADI's new online eLearning course, involving about 12 hours of slides on water pressure, buoyancy, nitrogen, etc . finally passing the last test one night at midnight. (Even bleary-eyed, it was hard to fail.)

Next I flew to Honolulu, where I'd arranged to finish the course with Ocean Concepts dive center. Although most beginners do the training in three days, I'd picked the two-day version, which meant completing all the pool skills plus two beach dives on the first day. Once I'd been fitted into an Aqua Lung wetsuit, mask, and fins, my instructor, Joanna, put me through three hours of mastering skills.

The pool turned out to be as scary as anything that came after: Even just eight feet down, even with some snorkeling experience, doing the mask-removal skill was freaky: Close eyes, take off mask, hold it out, resist instinct to breathe through nose, replace mask, purge mask by blowing out nose, open eyes. Fortunately, Joanna was a patient coach. After a long morning, the idea of swimming through crashing surf to make two beach dives was daunting. But I finned out, took some deep breaths, and dropped down 25 feet, and as soon as I saw all the trumpetfish, butterflyfish, and a spotted eagle ray patrolling the neighborhood, any jitters dissolved in the current. OK, I thought, this could get very cool.

On the second day, we did two boat dives, the first one 60 feet down to a wreck we could make out clearly from the surface.

Despite earlier difficulty, my ears had no trouble equalizing. Again Joanna signaled me through a checklist of skills, practicing things like a fin pivot—inflating the buoyancy-control device just enough to lift slightly with each exhale—and I had time left to explore, brushing a bit close to a rusty hole through which a gaping-mouthed moray stared back like a satanic cartoon fish. Next we tooled up Oahu's west coast to a shallow reef, where I navigated with a compass. When I popped out on the surface I was certified, which meant I was free to dive anywhere in the world, and to advance to higher levels.

But it was the next day, swimming for fun through the Makaha Caverns, that I became a diver. As we dipped in and out of a series of overhangs and grottoes, there were dozens of species of polychrome fish and, just chilling on a ledge inside one cavern, a sea turtle. I saw another and followed it along a valley in the seafloor. And then, looking up through an archway, I saw a third. It floated down past me, then gently doubled back and looked me square in the mask. If I had anthropomorphic tendencies, I'd have thought he was delivering some “Welcome to our underwater kingdom” message. But being more of a realist, I expect he was probing my potential as a food source. Either way, it's a different reality down there. —Will Palmer

How Snowboarders Become Ungrounded

I've been snowboarding for 12 years. But despite being able to tear down double-blacks and through waist-deep powder, I still find leaving the ground terrifying. Ollies, boxes, rails, and the biggest of all terrain-park horrors, the halfpipe—they haunt me.

Which is why I'm shaking in my black freestyle boots right now. I'm standing at the top ofa 22-foot halfpipe on Oregon's Mount Hood Glacier, hoping to find the courage and skill to drop in and fly over the lip on the opposite side. “Halfpipe riding is probably the most technical discipline in snowboarding,” says my coach, Reed Silberman. “Any imperfections in your form will come out.”

Um, thanks?

Silberman, 33, is head coach at Windells, a 22-year-old ski-snowboard-and-skateboard camp that, thanks to the glacier, stays open year-round. More than 90 percent of all X Games snowboard medals have been won by athletes who passed through Windells, including Shaun White.

My goal was more modest. I showed up for six days of private instruction last June hoping simply to learn to soar—no tricks or style points—out of the pipe. My lessons began on some blue and green runs with fundamentals, going over things I had forgotten or long ignored, like keeping my shoulders parallel to the board and bending my knees more.

When rain ate at the snow and ice which it did for half my stay—Silberman took me to a vert ramp in Windells's 184,000-square-foot skate area to work on “pumping the transitions.” In a halfpipe, you build speed by crouching as you enter each curved transition and extending on the flat bottom and the vertical sections of each wall. I managed on the skateboard but had a much tougher time on snow, which has a lot more variables. If I turned my shoulders, I lost balance and fell short on the far wall. Same thing if I made a sloppy turn, crouched late, or sprang early—time and again I ended up stuck low in the pipe's trough.

I found more success outside the pipe. After lessons on weight distribution and body alignment, Silberman eventually had me doing ollies, 180s, and box slides over small jumps and obstacles. The trick, I realized, was less about learning the skill than knowing I already had it. If I approached an obstacle confidently and fully committed, my momentum would simply carry me over. As for landing, that just involved being on the snow, which has never been my problem. The last day would be my one chance to put this all together in the pipe.

But after five hours, I still haven't. As my fellow campers spin below me under the June sun, I drop in for my last run and am shocked when I can suddenly see over the lip on the far side. Unfortunately, only my head makes it that high. With my board stalled about a foot below, I do a quick ollie and slide back down. So I didn't air it out over the pipe, but I can catch air now. And I plan to spend a good part of this winter above the lip. —Alicia Carr

The Dog Shouter: Training the Obedience Trainer

“Whiskey.” Mike Stewart, the owner of Oxford, Mississippi's Wildrose Kennels, gives the retrieve command flatly, as if he's ordering a round, and the yellow Lab at his left knee fairly launches onto the Colorado sage flats after a scented dummy. But a few paces in, Stewart peeps a whistle and Whiskey skids and sits.

“Drake.” The black Lab at Stewart's other knee uncoils and lines past Whiskey before Stewart stops him with the whistle as well.

“Whiskey, back.” And Whiskey is off again, snatching the dummy and returning it.

Alas, neither of these genteel all-stars is my eight-month-old chocolate Lab, Danger, whom I've brought to Wildrose's new summer facility in Granite, Colorado, to mold into a dependable pal for hunting, skiing, fishing, and mountain biking. No, while Stewart demonstrates the results of his low-force training, Danger—a Wildrose-bred UK retriever, like Whiskey and Drake—is an intermittent and rebellious glimpse of brown in the swamp willows behind us.

Stewart, 54, the son of a horse trainer, stands six foot two and looks as imposing as the Ole Miss campus-police chief he was in the eighties. His first career shows in the way he interacts with dogs; he's calm, direct, and fair, and he reacts swiftly and assertively when pups challenge him. His philosophy—he calls it the Wildrose Way—was developed over the past 30 years around the pack-leadership obedience techniques that pop-culture dog gurus like Cesar Millan espouse.

It works like this: Establish yourself as the dominant dog by doing things like eating first, leading through doorways, and carrying yourself like an alpha. That means cutting out the indiscriminate cooing, petting, and stick throwing. It's these last few that get everybody, including me. When I tell Stewart that my girlfriend squeals at Danger and twirls his ears, he says, “I can't change the dog.

I can only change the people. Send her up here next week and I'll train her.”

When I finally manage to get a leash on Danger, Stewart leads me through some basic heeling drills: “Danger.” Wait for eye contact. “Heel.” When he's at my knee: “Good dog.” If he gets too far ahead, snap the lead or reverse directions. Reinforce good habits and correct the bad. It works: After a couple of days, Danger is making consistent eye contact and acting calmer, though ingraining good habits takes months and years.

If none of this sounds particularly advanced for a hunting dog, that's because the majority of the training for any working retriever comes down to obedience. All dogs, be they hunting stock or pound puppies, are smart; the important question is whether they're interested in pleasing their handler. Danger is prone to relapses, and not long after our trip to Wildrose, that tendency results in three costly trips to the vet—for a barbed-wire cut, a close call on a pulled ACL, and a deworming after what we'll call the Diaper Incident. The cause was the same in each case: out-of-control dog, untrained owner.

Now I take obedience seriously, if only for Danger's health. And for his part, he thrashes around in the brush with more purpose and always returns with the duck—my reward. —Grayson Schaffer

One Ultra Step Farther for Mankind

“How many of you are running your first ultra today?” asks Wendell Doman, the event coordinator at California's Carmel Valley Trail Run.

A handful of us meekly raise our hands, and the crowd of about 170 fellow runners—a mix of 8K, 19K, 25K, and 50K racers—offers a warm cheer.

“Good luck to you, and have fun,” says Doman. “This is one of the hardest courses we offer.”I look up at the 5,000-foot Santa Lucia Mountains, then over at my two-woman support crew—wife, Christian, and nine-month-old daughter, Olive. They're waiting for my estimated finish time so they know how many hours they have to kill while I try my latest incomprehensible stunt.

“Maybe come back in six hours instead of five?” I offer. Christian glances at me with equal parts pity, bewilderment, and halfhearted tolerance. I know this look. If it were accompanied by words, it would say, “Tell me again why the hell you're doing this sweetie.”

The race begins, leaving me with a lot of time to ponder the answer. Why am I doing this?

I have always been hooked by the simplicity of running. Put on shoes. Run. No expensive purchases or equipment maintenance necessary. Over time, running without a goal—known as jogging—wasn't enough, and for eight years my wife has supported my strange quest to raise the bar. It began with a couple of half marathons, a road marathon, and, finally, a few rugged trail marathons. I was never a serious competitor, but I finished, and after every race I was haunted by the same question: Could I go any further?

The logical next step was the 50K. At 31 miles, it's the starter's ultra, the gateway drug to long-distance addiction. I figured I'd simply adapt the marathon training plan I'd always used: regular weekday runs of three to seven miles, Saturdays off, and one progressively longer run every Sunday. To carve out training time, I'd take Olive with me, pushing her in a BOB stroller. She'd sleep; Christian would sleep in. Win-win. It all went perfectly until, late in my training, I made a naive calculation. Since I was pushing a stroller that was increasing in weight each week, maybe my long runs didn't have to be quite as, well, long.

So I'm not exactly prepared as we set off for the race. Within 300 yards, the course takes a right turn and ascends 900 feet up the valley floor, followed by a brutally steep downhill. All told, the race includes 8,600 feet of elevation gain over two laps, which means that as the 25K racers are trading war stories and high-fiving at the finish, I'm stocking up on energy gels and steeling myself to go again.

I see only three other runners during the next three hours. I gobble salt tablets like peanuts to combat calf cramps, and walk backwards down one hill to alleviate the pounding. But mostly I'm in a groove, just planting one foot in front of the other. And that sensation is really why I run. I've tried meditation for years, but the closest I've come to Zen clarity is while running. The longer I go, the closer I get. Thoughts are gradually stripped away, like the chaotic layers of paint on a Jackson Pollock, until all that's left is a blank canvas and the things that really matter. Family. Wife. Child. Salt.

I shouldn't need six hours of exhaustion to realize what's important, but, hey, it works. And the epiphanies are addictive. —Chris Keyes

Fightin' Words in the UFC Cage

I step inside the cage, or octagon, or what my mother once called “that prison-looking thing,” on the floor of the Albuquerque Convention Center. I hear the cheers of 2,500 mixed-martial-arts (MMA) fans, though the stage lights make it impossible to see beyond the black chain-link fencing that surrounds me. They've come for FightWorld MMA 16 International, a night of 13 amateur and professional bouts. I'm in the opening fight. A referee wearing black plastic gloves gives instructions in my ear, but I can't make them out. He steps to the center of the mat and, with no ceremony, yells “Fight!”

I'd always wondered—and I know I'm not alone in this—how I would handle myself in a fight. The closest I'd ever come was a heated game of king of the hill in sixth grade. As an adult, would I have the balls to repeatedly punch another man in the face or, perhaps more important, be on the receiving end of the same?

Last spring, I explained my ambitions to Tom Vaughn, co-owner of FIT NHB, an MMA gym in Albuquerque, New Mexico, near my home in Santa Fe.

I was 28, moderately active—I hike most weekends—but a decade removed from my peak fitness (high school football) and carrying only that 0 1 fight record from sixth grade. “We'll need to do some work,” Tom said, looking me over. But he agreed to train me.

Our first session began with simple chokes and striking, then Tom demonstrated a defensive counter called “shrimping.” To practice it, he had me lie on my back and push off with one leg while simultaneously turning on my side. The goal is to recover “guard,” a neutral position in which one fighter has his legs wrapped around the other's waist. But with no one on top of me, I flopped around like a fish on the bottom of a boat. After a few minutes, Tom mercifully stopped me. The next day, his wife, Arlene, who is the gym's Thai-kickboxing instructor, had me practice basic kicks on the heavy bags for an hour. I felt on the verge of puking several times.

Eventually, though, I settled into a routine. Three days a week I drove the 60 miles to Albuquerque and began with an hourlong kickboxing class that often left me bruised and bloodied. The final 15 minutes were reserved for conditioning —wheelbarrows, squat-hops, and push-ups. Always push-ups. Next, grappling, which became my preferred style. (MMA fighters are generally either strikers or grapplers.) Tom would demonstrate a move, like an arm bar, heel hook, or triangle choke—each one a submission move that forces an opponent to surrender before a bone snaps or he is choked out—and then I'd practice with a partner. By the end of each back-to-back session, I was spent. After one particularly brutal day, my biceps were so sore that I had to brace one arm with the other just to brush my teeth.

But I was improving. After three months, I'd lost 15 pounds and was holding my own in sparring sessions. I grew more confident. Friends joked about starting bar fights so I could practice. Then one day at the gym, Tom pulled me aside. “I got a fight for you,” he said, “in two months.”

That had been my goal from the beginning, but suddenly, with the prospect of someone training specifically to kick my ass, it became visceral—Holy crap, I'm really stepping into that prison-looking thing. I immediately ramped up my training. Five days a week in Albuquerque. Runs in the mountains. Hundred-yard sprints on a football field. Mock fights at the gym. There are plenty of motivators if you need a reason to work out: physical fitness, ski season, vanity. But nothing focuses you like the knowledge that your survival could actually depend on it. By the time fight night arrived, I was in the best shape of my life and, at 167 pounds, nearly 25 pounds lighter than when I'd started.

I met my opponent for the first time at the weigh-in, at a chicken-wing restaurant the day before the fight. Alex Gumaer, 24, from Oregon, was a first-time fighter too, with a chin-strip goatee and a reddish topknot that made him look like an Irish gremlin. Absurdly, I wished him good luck.

From that point until the start of the fight, a combination of nerves and adrenaline short-circuited my body. I was scared, but more than anything I was excited. Most fighters train for a year or more before stepping into the cage; I'd had half that. My modest goal: survive, and maybe make it past round one.

The first punch hits me with a vicious thud, just one second into the round. I hear it, and the crowd's reaction, but I don't feel a thing. Blood is pouring from my nose, and my eye is swelling up. But I recover and manage to score a takedown. We spend the rest of the three-minute round tied up on the ground, me in the dominant top position, scoring hits to Gumaer's ribs. Round two unfolds almost identically, minus the hit to my eye, and by the start of the third I'm ahead on the scorecards. We go to the floor again. But Gumaer gets top position and starts swinging wildly at my head.

The first two rounds seemed to be over in a matter of seconds. But now everything slows down. I block with my forearms and try to shrimp my way to safety. I hear the ref yelling, “Get out of it! Get out of it!” But I'm caught against the cage; no room to maneuver. And 34 seconds into round three, he calls the fight.

After the official announcement, I step out of the cage, onto the concrete floor, and see the crowd for the first time. Tom is next to me, his normally intense eyes betraying, I think, a sense of pride. Arlene wipes my face with a towel. “Nice work,” she says, and gives me a quick hug. I feel a strange satisfaction rising in me. It's the first emotion I've felt all day.In the locker room afterwards, a doctor comes in to check on me.

“You all right?” he asks, feeling my bruised and bloody cheekbone for fractures.

“Never better,” I say.

I mean it.

—Ryan Krogh

Laser Sailing Crew of One

The puff—20 knots plus—came in hard and fast from behind me. I reacted quickly, arcing my body out farther over the indigo Atlantic water, my toes hooked under the hiking strap as I strained to lever the Laser dinghy upright. I bore off farther downwind, spray smacking me in the face and the planing hull humming the sweet sound of speed. Everything was in perfect balance. Just as I started to mumble self-congratulations, the 14-foot boat snap-rolled back on top of me, and I was underwater.

In Laser-speak, it is called a death roll, and I was sick of my talent for executing it with predictability in strong wind. That's why I was at the Laser Training Center, in Cabarete, a small town off the northern coast of the Dominican Republic. I had started racing the Laser—a popular high-performance dinghy that's been around since 1972—a year earlier on Chesapeake Bay. But I needed some good coaching, and if you are a Laser wannabe in search of technique in the gnarly stuff, the Laser Training Center is the place to go. “Almost every afternoon, the wind fills in and blows hard,” says Ari Barshi, an Israeli who opened the center in 2003. “And you get big waves.”

A Laser is not a solo dinghy to relax in, like a Sunfish. It's an overpowered and finicky beast that is eager to dump you, hurt you, and embarrass you. Even the best in the world sometimes end up floundering underwater, and to master the boat requires endless practice and a willingness to hike your body out in a continual sit-up that sets your abs screaming and thighs trembling. But when you get it right, it's a gasping thrill ride. Big wind and waves make Cabarete perfect for learning how to tame the Laser, with a flatwater training area inside the reef break and heart-pumping big rollers on the outside. The conditions are so good that the Laser Training Center is a regular midwinter tune-up for many world-class Laser sailors. Which means that Javier Borojovich (a.k.a. Rulo), the head coach—who spent five days last February teaching me, a family from Canada, and a couple of curious walk-ons how to stay upright and sail fast—can pass on all the latest techniques and tricks used by Olympians and pros.

“Don't let the sail out too far, and stay ready to counteract the roll,” Rulo said, slaloming downwind with abandon as he showed me how to throw my weight across the boat to avoid a death roll. Video, good coaching, and day after day of screaming winds worked wonders. I am no longer the death-roll king. —Tim Zimmermann

Skillhunting 101: The Master List of Master Classes

You’ve learned the basics. Now take your game to the next level with these top schools.

Kayaking

Nantahala Outdoor Center; Bryson City, North Carolina

Nantahala was founded in 1972, the year of whitewater's Olympic debut, and has been using Olympians as instructors ever since. During the five-day Advanced Creek Week course with U.S. Freestyle Team paddler Andrew Holcombe ($1,099), you'll learn crisper eddy turns and combat rolls in Class III runs.

Sailing

Boston Sailing Center; Boston, Massachusetts

With I-93 now passing underground, Boston feels like a proper harbor again. At the Sailing Center, a 30-year New England stalwart, you can start with courses in electronic navigation ($350) and night sailing ($295). Advanced Sailing ($795) covers tuning, spinnaker handling, and navigation over five days. Then learn coastal passage-making on your way to Nantucket (five-day cruise, $1,290).

Surfing

SurfCoach USA; Oceanside, California

Get ready to compete. With former pro Sean Mattison guiding you from the lineup during his weeklong Boot Camps ($375), you'll polish your backhand cutbacks all morning and run mock heats in workable breaks and hollows. You'll get a surf-specific workout plan, too: Mattison preaches physical training and stretching to keep you primed for your next session.

Saltwater Fly-Fishing

Florida Keys Fly Fishing School; Isla Morada, Florida

You've waded western rivers and can drop a pale evening dun in front of an 18-inch rainbow. Now head to the Florida Keys, where eight-time Grand Champion angler Sandy Moret andfly-fishing icon Flip Pallot will prepare you to battle 150-pound tarpon. Small-group weekend lessons ($1,250) teach casting technique and strategy; actual fishing comes later ($585 per day).

Wilderness Survival

Boulder Outdoor Survival School ; Boulder, Utah

BOSS's Seven-Day Field Course ($1,350) covers friction fires, water purification, navigation, and thermodynamics all with only basic equipment. Think you could be the next Les Stroud? See how you fare on BOSS's more strenuous (and minimalist) 28-Day Standard Field Course ($3,875), which they've been teaching in southern Utah for 40 years.

Skiing

National Alpine Ski Camp; Mount Hood, Oregon

“We get the fanatics,” says NASC director Brad Alire. Well, who else would go to a ski school that runs from June to August, on the glacial ice of Mount Hood, a training site for USSA team racers? At the ten-day Ski Training Master's Program ($1,995), you'll fine-tune steering, edging, and pressure control, hitting nearly 500 gates a day.

Cycling

; Various Locations

This is what it's like to be a pro. A veteran wrench has your rig humming, and Chris Carmichael has just personally set your target= watt range. If you flat, the SRAM support vehicle is there. Meanwhile, a fleet of coaches helps you improve pacing and dishes tips on group-ride dynamics. Weeklong spring training camps ($4,000) load up on miles; two-day performance testing ($1,000) hones technique.

Snowboarding

; Whistler, British Columbia

The same folks who developed Whistler's legendary Dave Murray Ski Camps have turned their attention to boarding. The two-day Quiksilver FreestyleFreeride camps ($229) work slope and park technique on terrain that ranges from GS lanes to superpipes.

Mountaineering

; Talkeetna, Alaska

AMS's 12-day advanced mountaineering course ($2,850) is run like an expedition. On day one, a ski-equipped, fixed-wing aircraft drops you deep in Denali National Park, and the coursework is full-time from then on, from glacier travel and crevasse rescue to route finding and rock, ice, and aid climbing. They also teach guide courses (12 days, $2,850).

Rock Climbing

; Boulder, Colorado

From Eldorado Canyon to the Flatiron Range and Rocky Mountain National Park's Lumpy Ridge, Boulder's perfect granite and sandstone is a great place to step up your climbing. And CMS, which traces its guiding lineage to 1877, is the best place to start. Its one-day Big Wall Clinic ($170) teaches hauling, hygiene, and hanging camp, while the Crack Clinic ($170) gets you hand-jamming without pain.

Triathlon

; Various locations

Eight-time Ironman world champion Paula Newby-Fraser is among the stars who teach three-day camps ($795) at the sites of Ironman events, seven to nine weeks before race day, to get you fit and familiar with the course. Five-day winter training camps ($1,145) include video analysis, an anaerobic-threshold test, and lots of miles. Newby-Fraser and coaches like '97 world champ Heather Fuhr and former pro Roch Frey can also be hired for a weekend of one-on-one ($3,500). —Matthew Fishbane

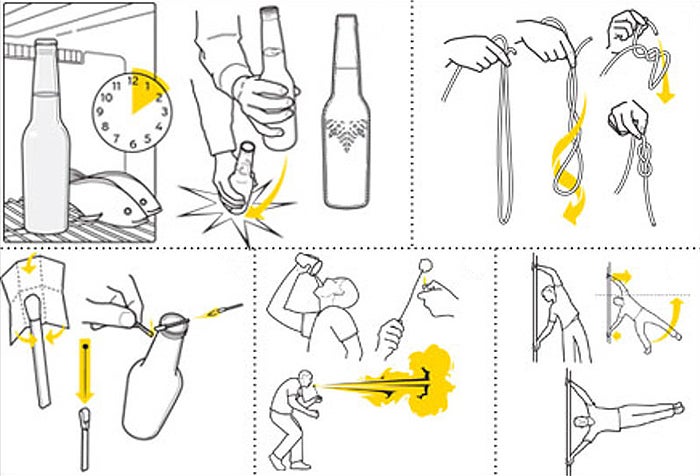

Stupid Party Tricks that Might Not Kill You

1. Instantly Freeze a Beer

Place a bottle of beer in the freezer for about two hours and don't agitate it. Thanks to a thermodynamic effect called supercooling, the stillness will allow it to remain liquid below its freezing point. Take it out and gently tilt it so your friends can see it's not frozen, then remove the cap and firmly slam the bottom of the bottle on the counter. It will freeze instantly. Now take someone else's beer, since the frozen one is useless.

2. Tie a Knot One-Handed

Fold a piece of rope over on itself about two feet from the end. Grab both strands in one hand, near the end, so that you have a loop hanging down to the ground. Holding it like a lasso, begin to twirl the loop at your knee. It should start to twist. As soon as the second twist enters the loop, pop the rope up into the air and pass the short end through the hole in the loop as if you're threading a needle. Voilà: one-handed figure-eight knot.

3. Turn a Match into a Rocket

Tightly wrap the head of a paper match with a small piece of tinfoil. Take a needle and pierce the tinfoil at the very tip of the match head. Place the match on the mouth of an empty bottle. Hold a flame to the tinfoil for a few seconds. Liftoff! (As with most tricks, this one will impress children most.)

4. Breathe Fire

Everybody loves fire. Which is why this trick is so awesome: You get to blow it like a dragon. First you need a fuel source; a cotton ball soaked in white gas and stuck on the end of a wire works well. Now pour half a cup or so of cornstarch into a cup. Head outside, light the cotton ball, take a big mouthful of cornstarch, and blow it at the flame. The good thing about using cornstarch rather than, say, alcohol, is that it's flammable only when highly oxygenated, so you don't have to worry about igniting your esophagus. Which is nice.

5. Be a Human Flag

Technique, practice, and a sturdy, chain-link-fence-size pole are all you need. Your bottom arm—elbow locked, palm facing backward, thumb pointing down—is the brace, pushing into the pole. You'll pull yourself up with your top arm—four to five feet above the other, palm forward. Get a good grip and then hoist your legs with a hard kick. Go horizontal and try to hold it. The world record is just under 40 seconds. You should expect about two.

6. Sabre a Champagne Bottle

Remove all foil and wire from a chilled bottle and find the seam running from top to bottom. You're going to use the flat edge of a butcher knife to strike the glass lip right where it meets this seam. Point the bottle slightly up and away from anything you care about, with the seam up. Run the blade along the neck a couple of times to perfect the motion—striking perpendicular to the neck. When you're ready, one forceful sweep of the knife should send the lip—with the cork still inside—flying away cleanly.

7. “Levitate”

Wearing loose pants, stand with your feet together and your back at a 45-degree angle to your audience. Press your heels together and lift onto the toes of the foot that's away from the audience. Keep your other ankle cocked, so it rises parallel to the floor. The dimmer the light, the better. Ditto the audience.