As always, Oscar Wilde said it best. “Morality, like art, means drawing a line someplace.” I'm drawing mine on the cobbles of Paris's Champs-Elysées this past July 23, the last time there was a major bike race I could pretend to believe in.

I didn't arrive here easily. Since July of 1989, when I charted in the Tour de France on my bedroom wall, cycling has been the source of all my sporting heroes. I still have an autographed poster of Tyler Hamilton in my office. Wait a minute . . . Until just now, I still had an autographed poster of Tyler Hamilton in my office. And that's two years after he was caught with someone else's blood in his veins. So it breaks my heart to say this, but to hell with pro cycling. Giving those guys the benefit of the doubt involves a moral compromise I can no longer make.

This year's Tour strained credulity right from the start. On the eve of the race, arguably the biggest drug scandal in sports history resulted in the ejection of all the top

This wasn't exactly taking place in a vacuum. Amphetamines have been around cycling for decades, and a drug bust in 1998 nearly shut down the entire Tour. Still, this season was the hypodermic needle that broke the camel's back. Look at the three grand tours—May's Giro d'Italia, July's Tour de France, and September's Vuelta a España. Basso so crushed the field at the Giro that the third-place finisher called his performance “extraterrestrial.” But if the allegations that got him booted from the Tour prove true, he's been as doped up over the years as Courtney Love. Only less honest about it.

Then came the Tour: a new American hero and a Stage 17 ride that briefly ranked alongside the Miracle on Ice for all-time-great sports performances. Before the goose bumps had settled, though, the moment , replaced by a crash course in testosterone and lame excuses. A month later, the Vuelta started without 2005 winner Roberto Heras, who was banned from cycling after failing a doping test. That's the sport's three marquee events, all drowning in a morass of hormones and refrigerated blood.

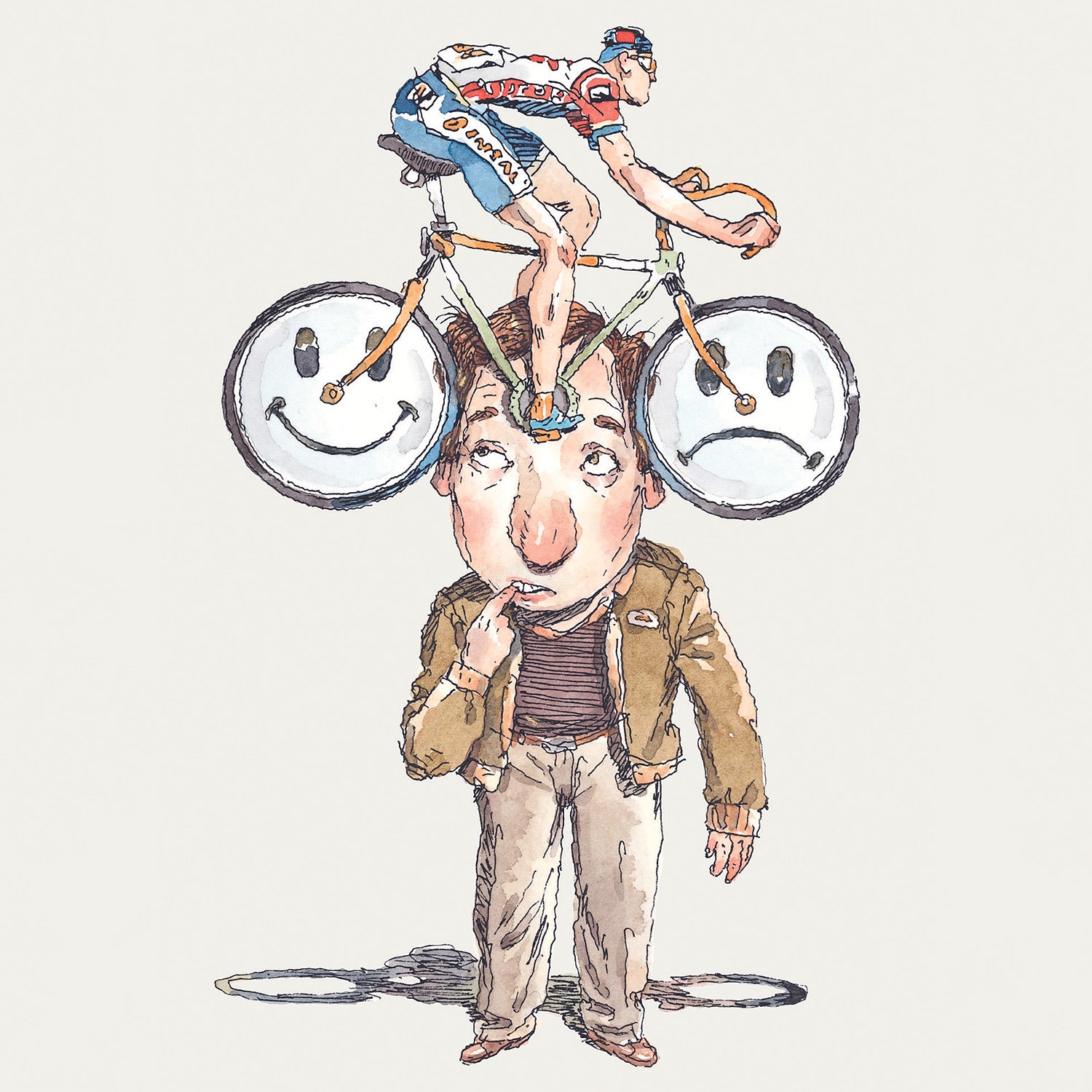

Pro cycling has become sporting porn, all artificial enhancements and superhuman performances in something that’s better natural.

It gets worse. Of the 190 riders who started this year's Tour, 105 went through doping controls, and 13 tested positive. But 12 of them—the 12 not named Floyd—had medical exemptions. In fact, 60 percent of the tested riders had notes from their doctors for afflictions like asthma and inflammation. Really? More than half the field in the world's toughest race have medical conditions severe enough to warrant banned substances? Dirty bastards. Also, none of the guys who were kicked out before the start had actually tested positive; they were snagged in a police sting. So if guys who test positive have medical excuses, and guys who test clean turn out to be doping anyway, professional cycling is rotten to the core. It's not a few bad apples. It's a whole crooked apple tree growing out of the muck.

Problem is, I really like them apples. Even after Landis's meltdown, I still followed the Vuelta every day. When Kazakhstani rider Alexandre Vinokourov—long one of my favorite cyclists—grabbed the lead with a monstrous ride near the end of the race, I felt a rumble of the familiar excitement. But then I began to doubt that he could ride like that clean. Then I felt bad for doubting a guy who's never tested positive. Then I remembered that a lot of dirty riders have never tested positive. Then I just couldn't watch anymore. Cycling had become sporting porn, all artificial enhancements and superhuman performances in something that's better when it's natural. Plus I was suddenly worried that someone might catch me watching.

I'll never stop riding, though. I refuse to let the cheats take away what has been the defining athletic pursuit of my life. Look, I used to love Woody Allen films, then he ran off with his lover's daughter, and now Manhattan creeps me out. But I still go to the movies. So if the pros want to pack their blood, slap hormone patches on their nethers, and trot out lawyer-vetted statements about how they've never tested positive for anything, fine. I'll be on my bike.*

*Unless Landis ends up winning his appeals, in which case I'll probably be right back in front of the television. In my room. With the door closed.

Cycling through the five stages of grief

- Denial: “There’s no way [insert cyclist’s name] would take drugs. Never!”

- Anger: “I can’t believe [insert “the French”] are trying to bring him down! They’re just jealous.”

- Bargaining: “If he did dope, it was just to level the playing field. He would never cheat to gain an advantage.”

- Depression: “The sport has lost its soul if even someone like him has to take drugs to compete.”

- Acceptance: “Yeah, I could see it. They’re all dirty.”