Jonny “Big Air” Moseley, 23, is rolling in a white 1997 Chevy Blazer down Squaw Valley Road, past the Resort at Squaw Creek, where there used to be a Jonny Moseley Suite, along the foot of the KT22 ski lift, which climbs to the Jonny Moseley Run, and into Tahoe City, past banners proclaiming “Congratulations Jonny.” He flips through a CD case, searching for tunes, when suddenly he remembers what he really wants to hear.

Opening the glove box, he withdraws a cassette, which he pops into the tape deck. A clicky studio synthesizer drum track comes on, accompanied by a twangy, spacey guitar. Then a gentle, rich voice begins to sing: “I'm a Muffin Man, I come from Muffin Land, I'm a puffin' lovin' Muffin Man.” It's a ridiculous song, reminiscent of Dr. Demento or The Gong Show, and not the kind of stuff to which Jonny — whose musical tastes veer toward the reggae of Bob Marley, the tropical hip-hop of Wyclef Jean, and the old school thrash of Pennywise — would normally listen.

“Dude,” Jonny says, grinning his wide-toothed smile beneath his yellow wraparound Smith shades. “That's me singing. I got totally trashed one day and went into the studio with this guitarist and he had me sing this song.”

“He's got muffins on his mind, He eats muffins all the time …”

He guns the V-8 engine and the Blazer lurches forward. “The guy wants to release it as a single.”

“Muffin Man”? Jonny Moseley's debut as a professional singer?

“I mean, if it were like the week after the Olympics, then maybe,” Jonny says. “That would have been sweet. I could have been, like, it wasn't about the skiing or the gold. It was all about 'Muffin Man.'”

He parks the car alongside a stone retaining wall, next to the Mandarin Villa Chinese restaurant in Tahoe City. “See, 'Muffin Man' has two meanings. There's like, muffins, like the kind you eat. And then there's muffins, as, like, girls. And I'm the Muffin Man. And this — “

Jonny points around him at the car interior, the stone wall, the parking lot, but what he is really doing is gesturing at his whole lifestyle — the gold medal he won at this year's Winter Olympics, his family's many houses and boats, his good looks, his killer smile, the crates of fan mail, the endorsements, the big post-Olympics income, the fame, the recognition, the whole golden life.

“This is Muffin Land.”

There is a specific geography to Muffin Land that includes the Moseley residence in Tiburon, Marin County, California; a ski cabin in Squaw Valley; and his family's houseboat on a private island in the Sacramento River delta. It includes Tiburon's Paradise Cay Yacht Harbor and the attendant Yacht Club, built by the Moseley family, as well as a compound on the Caribbean Island of St. Croix. There are also the numerous Marin County lots worth millions of dollars that were originally purchased by his grandfather, Tim Moseley, a prosperous inventor of nautical instruments. There are a Jeep Wrangler, a 1964 Pontiac Bonneville convertible, and the Chevy Blazer. There are yachts, speedboats, Waverunners, race cars, and motorcycles. There are repair shops, junkyards, and scrap heaps. There are also backhoes, tugboats, and dredging barges.

Born to this pre-Silicon Valley northern California elite, Jonny was shaped by a way of life that included winters in the Tahoe snow, summers boating on the bay or at the Saint Francis Yacht Club's island up on the Sacramento River delta. His older brothers, Jeff and Rick, were good athletes, competitive skiers and sailors; Jonny's father, Tom, a prominent developer and contractor, was always an avid skier and sailor, teaching his boys to be as at home in the snow and on the water as they were on dry land.

But there is also a mental space to Muffin Land, a state of achieved bliss that allows Jonny to move through life with a grace and poise rare in a 23-year-old. While most males his age have been sweating through the armpits of their white button-down shirts during job interviews or moving back home after graduating from college, Jonny's been having dinner with Cindy Crawford, or MTV VJ vixen Serena Altschul, or another famous, important, or totally hot-looking person. Never forget that Muffin Land is home to the Muffin Man — and Jonny is also about the ladies, about finding the ladies and calling the ladies and meeting the ladies and having a good time with the ladies.

Yet Muffin Land is also about being a great athlete, about being the number-one-ranked mogul skier in the world and about winning two World Cup overall freestyle titles, five combined junior and professional World Cup titles, and 14 World Cup events. It is about landing a radical 360 mute grab air at the end of the biggest run of your life and in the process revolutionizing your sport. It is about busting a version of that same jump for The Late Show with David Letterman in the driving rain on a cordoned-off New York City street. (It was Letterman who gave Jonny the nickname Big Air.) It is about appearing on ABC's The Superstars competition broadcast in April and surprising the field by finishing second, ahead of athletes like Kordell Stewart and Herschel Walker and Lennox Lewis. And it is most certainly about the gold medal he won with that spinning, skis-crossed jump in the moguls at Nagano — the jump that catapulted him onto Oprah, Rosie, The Today Show, and Good Morning America.

In short, Muffin Land is about success and accomplishment and amazing good fortune. And it is about its lone resident, who may or may not know the true value of the passport he holds.

��

��

Jonny has, in some ways, always been in training for assuming the mantle of Muffin Man. Being the youngest of three boys gave him a taste for competition early on; his brothers were brutal gamers who didn't cut Jonny breaks because he was the youngest. He had to make the same runs, jump the same moguls, and bust the same huge air as his big bros. And if he didn't tabletop that helicopter, they would let Jonny know he was a pussy.

“I always wanted to be the best,” Jonny says. “I think competition is key. At an early age, because my brothers used to work me, I realized what competition did, how it made me feel. I realized what it meant to me. I love the feeling of winning.”

He would take any dare, stand up to any challenge. His high school soccer coach at Marin County's elite Branson School used to sic Jonny on the opposition's best player, and Jonny would inevitably shut him down. “Jonny was always a good athlete,” says his mother, Barbara Moseley, who works as a real estate broker. “All the boys were good athletes. And that competition had to make Jonny even better.”

Jonny realized that he was, as one former ski coach says, “something special” after he won the junior nationals in Lake Placid for the first time: “I was 15 years old, and what I found out about myself was that I was good at competing, not just skiing. I loved that feeling. I liked being in the gate, all jacked up, nervous. I actually liked that feeling. I enjoyed competition. And when I found out about winning, I liked the competition even more.”

Initially, one of the perquisites of skiing was that it meant Jonny missed a few weeks of school every winter. But gradually, as Jonny racked up victories in major events, it began to seem possible that skiing was more than a means of skipping school and delaying college. “When I was 16, I won junior nationals again,” Jonny recalls. “Then next I won junior nationals and North American amateurs; I mean, I won everything in sight. For a couple of years there I was getting way better, I was getting awesome. And when I made the U.S. Ski Team, I realized I could get paid to ski.”

Happily, skiing just happened to be the thing at which Jonny was best. But whatever you threw at him — soccer, baseball, calculus, acting, auto mechanics — he would soon develop the appropriate skills. He was a solid student at Branson, a featured actor in productions of Oklahoma! and Our Town. And from his father, he learned the basics of auto mechanics and how to fix everything from a flat tire to a bilge pump. It was his father who taught him that Muffin Land requires constant vigilance and care — the houses don't maintain themselves, the cars don't fix themselves, the boats don't refit themselves. The good life requires a good pair of hands. And in a metaphysical sense Jonny learned that Muffin Land must be nurtured. You can't take it for granted. If you're the Muffin Man, then you gotta give something back to Muffin Land.

Today, Muffin Land is in disarray. There are boats and jet skis to be put up on trailers, trailer hitches to be fitted — and, for a party Jonny is throwing this weekend, kegs of beer to be procured and vodka to be stowed away. At the moment, the Muffin Man is struggling with one of Muffin Land's reigning edicts, a philosophy described by one of Jonny's friends, Trevor Pressman, as the Way of Mo. The Way of Mo is a sort of old-money, WASPy precursor of the DIY punk-rock ethic applied to hard-to-service items such as carburetors and tugboats. When something needs fixing in Muffin Land, you fix it yourself.

“My dad taught me that you don't go to the store for anything,” Jonny says. “No matter what it is, no matter how screwed up, you can somehow fix it right here. You just gotta roll up your sleeves and get busy.” You head down the block to the immense, concrete, Moseley-owned shed known as The Shop and find whatever tools and parts you need. Here on the San Francisco Bay waterfront just a few miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge, adjacent to the Moseley-developed Paradise Cay Yacht Club at the end of a vast, Moseley-owned cul-de-sac, The Shop is a forbidding industrial space where you suspect a resourceful engineer and a sufficiently innovative mad scientist could concoct a missile with enough throw weight to convince Indian nationalists to think about global, rather than regional, nuclear war. It is the sort of grimy, tool-rich environment to which every child who ever assembled an Estes rocket or fueled up a Cox model airplane dreamed of having access.

Right now, all Jonny needs is compressed air to inflate a flat tire on a decrepit trailer holding one of his jet skis. As he walks around The Shop floor looking for the air tank and compressor, he passes bushels of gaskets, crates of brake fluid, piles of spark plugs, engine casings, greasy bolts, plugged exhausts, rotted mufflers, and pieces of just about every post-World War II nautical or automotive part ever made.

But you have to be in The Shop every day, as Jonny has not been lately, to know where, say, the air tank might be. If you have been away, winning gold medals and hanging with Cindy Crawford, then you come back to The Shop and The Shop's randomness and chaos defeat you.

So Jonny shrugs, puts his hands on his hips, and takes a call on his StarTAC cell phone to give a cute blond directions to his houseboat party this weekend.

A few minutes later, driving back down the street in the Blazer, he runs into his father, driving his own Blazer to The Shop. (Members of the Moseley family seem to spend the day driving various trucks and sport-utility vehicles between various pieces of Moseley-owned property.) A conversation takes place, driver to driver, in opposite-facing Blazers.

“Dad, where's the air tank?”

Tom Moseley props his elbow on the truck door. “You know, if you were down at The Shop more you might know these things. Maybe Dooley has it.”

Dooley is a hippie who works around the boatyard. Dooley was last spotted cranking some Neil Young from the beleaguered speakers of his red Volkswagen bus as he started up the sputtering engine. Jonny drives over to Dooley's boat and reconnoiters, but the pump's not there, so Jonny climbs back into the Blazer and returns to his parents' garage, hoping that a can of aerosol flat-tire fixer might fill the trailer tire. But the one can of flat-fix that Jonny can find is an ancient specimen that emits only a gentle wheeze of fluorocarbons before it gives out. Another character-building lesson in the Way of Mo.

The flat tire sits in its divot, weeds growing up around it.

Jonny appears ageless — to look at the man you immediately think you have a sense of the boy. His brown, proto-mop-top hair; hazel eyes; pale skin flecked with soft freckles; protruding, masculine nose; and gentle, full lips give him a look similar to that of Tom Cruise circa Risky Business. (Rosie O'Donnell pointed out the similarity when Jonny appeared on her show.) And because of the easy physicality of being a professional athlete, he wears his looks with equanimity, becoming all the more handsome because he is not defined by his good looks.

Jonny is that rarest of ultra-successful professional athletes in that he manages to combine the supreme confidence required to shred at the highest level of his sport with a gracious humility that makes it impossible to begrudge him his accomplishments. “He is really cool about who he is,” says Shane Anderson, a fellow professional skier. “And he doesn't have to act big to make sure you know he's a big deal.”

��

A big deal he is — the biggest star of the moment in freestyle skiing, and on the verge of becoming the biggest star in all of skiing. (Perhaps only Hermann Maier — The Hermanator — and Picabo Street are in his class in terms of wide-breakout popularity.) Jonny was the first skier to cross over the street-styles of skateboarding and its winter cousin, snowboarding, into big-time competitive skiing. The crowd-pleasing 360 mute grab air that won him the Olympics, for instance, was a move lifted from snowboarding. These ingredients make him a marketer's dream. “Right now there aren't too many people who aren't interested in Jonny,” says Tim Vetter, Jonny's agent with Action Sports Management. “With him, it's not a matter of worrying about where the next deal is coming from; it's a matter of choosing the deal that's the most fun for Jonny.”

So far, besides his sponsorship arrangements through the U.S. Ski Team and his gear sponsors — K2 skis and Tecnica boots, among others — he is also affiliated with American Skiing Company, owner and operator of nine resorts nationwide. (“I think you have to go back to Jean-Claude Killy to find someone comparable,” gushes Skip King, American Skiing Company's vice-president of communications.) And Jonny is working on a deal with Polo Sport — a significant step, since it would be his first nonskiing-related mass-market endorsement.

The funny thing is, as you tour Muffin Land with Jonny, you begin to wonder how his life would have been any different if he had not won the gold medal. What if he were just Jonny Moseley, non-gold-medal-winning skier? What if he weren't a professional skier at all but just a ski bum — would he still be the Muffin Man?

“Some things have changed, there's no question about it,” Jonny says of life after the medal. “I mean my time is more valuable. My personal time is more valuable to me, and my time is more valuable to other people. But as far as the basic flavor, my life didn't change that much. I mean, I was loving life before and I'm loving life even more now. I've always been lucky, I mean, really lucky. It's all good. It's all so good I don't even like to think about how good it is. So let's stop talking about it. 'Cause if you talk about it and then figure out why it's so good, then from that moment it probably won't be good anymore. Like, if you have to think about it too much, how good can it be?”

But what is it actually like to be this successful at this young age?

“It feels great! I'm lucky, because I'm 23 and now I have the rest of my life to run with it, to do whatever I want. And that's an awesome feeling. I knew the minute I crossed the line [at the Olympics], this just put everything together. What else can I say? But believe me, not a second goes by that I don't remind myself: I'm really lucky.”

“People don't realize what kind of position you put yourself in on the day you decide you're not going to do the normal life and you're going to try to win an Olympic gold medal. At one point, it's like, wow, that's a noble goal. But on the other hand, when you're 17 or 18, you're putting yourself in the position of total satisfaction or total destruction. From where I come from to what I've done — I'm really, really lucky.”

Having abandoned the flat tire for lack of an air tank, Jonny has moved on to his next round of preparations for the weekend bash he is planning on the family's Tinsley Island houseboat for himself and 30 or so members of his posse. Sitting legs akimbo in whalebone corduroy cargo pants on the oil-slicked asphalt, he hunches over a soldering iron as he rewires a boat-trailer brake light. It is hard work, brutal on the back, and it is currently being made even more difficult by his mother, who has called from Virginia, where she is visiting Jonny's grandmother. He cradles the phone in the crook of his neck, assuring his mother that the upcoming party will not get out of control. He promises her that the two houseboats he has arranged and the numerous gallons of vodka and kegs of beer and speedboats and jet skis and wakeboards won't combine into a sort of high-octane aquatic cocktail that will leave Jonny's reputation tattered, psyche shattered, and guts splattered.

“No problem, it's gonna be OK,” Jonny says as he touches the iron to the resinous solder. “Like 20 people — 25 tops. You want the whole list? OK. Trevor and Josh and Beau and Mark and Toffee and Arman and … oh, fuck!”

The brake light Jonny has just connected isn't working. It just sits there, unblinking, a dull candy-red tribute to Jonny's inability to solder and talk on the phone at the same time. He says good-bye to his mother, who has passed the phone to Nana, his 85-year-old grandmother. “Hi, Nana. How are you?”

A few minutes later the cell phone rings again and it's Hathaway Pogue, an assistant to Dana Davis, daughter of billionaire Marvin Davis, and she's calling to ask if Jonny will participate in a charity auction. (“Next Item: A Ski Date with Gold Medal Winner Jonny 'Big Air' Moseley.”)

And then Jeff, his 29-year-old brother, comes over and tells Jonny he's doing a suckass job with the soldering, and then Jonny's father stops by to agree and tell Jonny he doesn't know what the fuck he's doing and how could a pantywaist job like this be taking this many hours, and Jonny tells his father it's because every passing car is filled with people who want to stop and talk to him and take his picture. And then, as if on cue, an elderly neighbor tentatively makes her way across the narrow lawn between sidewalk and street and asks Jonny if he would pose for a picture, “For my wee grandcousins in Ireland. They watched you win the gold on the Olympics and they love you, Jonny.”

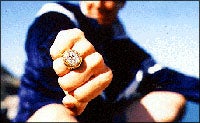

And Jonny stands and puts his arm around the old lady and flashes a hang-loose gesture at the camera and the brake light still isn't fucking working. And then the UPS lady shows up like she shows up every day with crates of ski parkas and Jonny Moseley posters and boxes of fan mail. Today she also has a special box, one that's smaller than the rest, from the U.S. Olympic Committee, and Jonny rips it open and pulls out an immense gold ring the size of a plum and slips it over his index finger. There are dozens of diamonds outlining the five-ringed Olympic symbol, and lettering saying “Gold Medal Winner 1998” along the sides. Jonny shakes his head. “I ordered the smallest ring they had when I got to Nagano,” he says, “because I didn't know if I was gonna win. I guess they upgraded me.”

And he tries to slip the ring off, but it's stuck. And the brake light still has to be fixed because it is on the back of the trailer that's hauling one of the speedboats up to Tinsley for this phat weekend that Jonny has been planning, like, since the minute he finished that Nagano gold medal run. And Jonny is filthy with brake fluid and soot, and his Kappa shirt is streaked black, and he realizes he's crossed the taillight wires and has to clip and resolder them. And Jeff cracks up: “One thing you can definitely say about Jonny: He's keeping it real.”

And then his dad comes back. He's found the air tank.

��

Jonny is the quiet, solid center of Muffin Land; he is the vessel of vast amounts of his family's love, his friends' respect, and his fans' adulation. As an athlete, Jonny's the winner of some genetic blackjack game in which he's been dealt nothing but aces and faces. Nevertheless, his work ethic when in training and his deep aversion to complacency are the things that pushed him past simple excellence and made him nonpareil. “He works 50 percent harder than any other person on the tour,” says Cooper Schell, the U.S. Ski Team's moguls coach. “He does everything possible that he can do to succeed.”

It was his superb conditioning that surprised those outside the sport of skiing when Jonny took second in ABC's The Superstars competition. The most striking segment had Moseley lining up against Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Kordell Stewart for an obstacle-course race entailing a climb over a wall, a tire drill, a blocking dummy, a high jump, and hurdles. Stewart, at 6-foot-1 and 212 pounds, was all angular slabs of bulging muscle beneath a tank top, while Jonny, at 5-foot-11 and 180 pounds, looked like your average-size frat boy. Moseley handily beat Stewart in a mad dash down the course.

As an amateur, Jonny's pure athletic skill and competitive drive had been enough to carry him to the podium. But when he went out on the World Cup tour, he admits, “I just got smoked.” At first he thought that what was required was merely better conditioning and greater strength. “I went and I got strong,” he explains. “I just started working out like a banshee, you know, hardly skiing. To some degree, it helped.”

It took another year for him to realize that in order to become good — “I couldn't go out and win an event at will, and that's what I consider good” — he would have to become a better technician on the slopes.

So the summer before the 1997-1998 World Cup season and the 1998 Winter Olympics, Jonny moved into Schell's house near Mount Hood, Oregon. “Coach Cooper took it on like a mission,” says Jonny. “He just engineered everything, studying videos and getting it down to a science so that he could figure out what was wrong with me. There was just something that wasn't clicking.” They agreed that Jonny needed to improve on the moguls, during the tight turns that constitute the technical portion of a freestyle run.

And then there was the psychological training. “We discovered that for me there was a difference between stress and pressure,” Jonny says. “Stress is when you're out on the hill training and you're doing your best runs and you look up and you know there's some other dude out there that's got mad skills that are better than you. There's no way you can be relaxed and try to compete well when you're under stress. But pressure is when you know you have the skills, when you know you can win, but you got gnarly butterflies. Then it's just a matter of turning that into frickin' power, you know, just going for it and letting it flow.”

The key to winning, Jonny discovered, was to ski to ski, not to ski to win. As long as he loved skiing, his athleticism and the hard hours spent working on technical skills would allow him to make repeated trips to the podium.

This off-season, however, has been more casual for Jonny. His usual training regimen has been thrown askew by the demands of celebrity. And though never a party animal, he has been known to have a soft spot for certain substances that after the Nagano Games were commonly associated with Canadian snowboarders.

“I used to bake once in a while,” he says of smoking marijuana. “But never when I was in training, and never when I was less than three months out from the tour. The main reason I don't now is because of the drug testing. Before the world championships, at the Olympics, you get tested, and when you're on the U.S. Ski Team they test you all the time. So I don't need that hassle, that reputation — my sponsors would hate it. Same thing with drinking. If I got a DUI, then there'd be all that bad attention. I mean, if I didn't have to worry about the testing and the press, I think I'd smoke more pot. I don't take any of the hard stuff.”

And the big party this weekend?

“We'll see,” he says. “But it's definitely the kind of atmosphere — old friends, no responsibility — where it's tempting.”

This is one of those days, one of those beautiful northern California days, when the air is clear and crisp like it's being pumped in from some cosmic purifying unit that is invisible beyond the horizon, and the tingle of it is making everyone feel giddy at the upcoming weekend and the party on the houseboat up on the Sacramento River delta. Even the Muffin Man has got the feeling as he helps load a keg of Budweiser into the back of a friend's Ford Expedition.

“It's gonna be wild, a total rager,” Jonny promises. “This is the first time I've gotten to hang with my friends since the Olympics.”

Towing ski boats and jet skis, the caravan of sport-utility vehicles, with Jonny's Blazer in the lead, sets off over the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge on its way to the delta. Along the way, Jonny calls the owner of a sporting-goods chain in the area and pleads with the man to let a certain young blond female named Melissa off work for the weekend so she can come up to the delta.

“I'm having a party,” Jonny says into the phone. “And Melissa tells me she has to work and she can't get the day off. I think she'd have a great time up there if you could just give her the day off.” The owner of the company is unrelenting.

Jonny hangs up, disappointed. “I blew it,” he says, shrugging. “I should have been harsher. The guy wants me to do an appearance for him. The least he could do is let this babe go for the weekend. Dude, what I should do is get my agent to call him back and tell him, you know, it's one of those scratch-my-back-and-I'll-scratch-yours deals.”

Instead, Jonny's buddy Trevor, sitting in the passenger seat, calls back and pretends to be Jonny's agent.

“I'm calling on behalf of Jonny Moseley,” Trevor says in his best cigar-chomping agent's voice. “And Jonny feels it is very important for Melissa that she come and experience this weekend with Jonny. Jonny hates for Melissa to be missing out on what promises to be a very exciting and rewarding time for her. And frankly, between you and me, Jonny is not happy about this.” There is a pause, then Trevor hangs up.

“No muffin?” Jonny asks.

“No muffin.”

��

The Saint Francis yacht club owns an exclusive enclave of the elite that's hidden away on private Tinsley Island in the middle of the Sacramento River delta. The sumptuous houseboats, verdant green lawns, bocci courts, swimming pools, and barbecue pits are concealed from the surrounding freshwater inlets and estuaries by shrubby atolls bearing such inviting nicknames as Dogshit Island. If you didn't know this place was here, or if you weren't a guest of a member, then you would never find it. The location and memberships, as well as title to the valuable houseboats and slips, are passed from generation to generation. Jonny's grandfather was one of the Saint Francis's charter members in the 1950s. He bequeathed his prized slips to his son Tom, whose kids, Jonny included, have been coming here since they were little.

It's the bejeweled heart of Muffin Land. “This is a special place for me, a very cool place,” Jonny says as he powers up the channel in his family's ski boat at the head of a small regatta consisting of Jonny's buddies in attending jet skis. “I mean, look at it. Awesome, huh?” The Moseleys' mooring is one of the finest, with afternoon sun striking the deck while the interior of the yellow two-bedroom houseboat is shaded by sycamore and pine trees along the shore. The sun casts the water in buttery golden light that illuminates the entire placid waterfront like a movie set.

A keg is tapped. Jonny catches up with old friends. Beau and Josh, Trevor and John, Toffee and Jeff, these are the guys he grew up with, attended high school with, played baseball and soccer with. They are good-looking kids with ripped stomachs and chests and handsome, chiseled features; these were the popular kids in high school, and now that they've all gone on to California's elite colleges — Stanford, Cal, UCLA — and are starting their careers, they seem flush with potential and vast promise. Jonny's success as a gold-medal athlete serves as some sort of precursor in most of their minds for the inevitable success that must await them as well.

“You're a superstar athlete,” Trevor tells Jonny. “I'm gonna be a film director, Beau's going into advertising, Jeff's gonna be a rock star, and Josh is going to be a sportscaster. When we all make it, it's gonna be like this powerful little network.”

More boats pull up alongside the houseboat. The deck becomes crowded with revelers, all hoisting plastic cups of keg beer or sipping vodka fizzes. His brothers are there, his friends, even his first high school girlfriend, and the vibe is one of celebration and respect.

“After I won the gold medal,” Jonny says, “I couldn't wait to get home and celebrate with my friends. That's what I wanted to do more than anything. The other stuff, the Letterman and TV stuff, that was cool, totally cool, but this is what it's all about.”

That afternoon, Jonny heads out for a spin on a brand new Kawasaki 1100 jet-ski that he won — along with $20,000 — in the The Superstars competition. The late-afternoon water is glassy, and the wind shimmers through the reeds lining the banks. Jonny rips huge curls through the water, forcing the jet ski into high-speed skids across its own wake. He's deep into it now, in the heart of Muffin Land, burning through the water going nearly 55 mph aboard a jet ski that he won, basically, because he's the Muffin Man. And later there will be wakeboarding and water-skiing and diving into the club's pool while the other club members applaud his outrageous dives. And there will be a touch-football game and bocci and a barbecue.

There's also this cute blond with a cruel face down from Tahoe, and later there will be her as well, and the two of them retreating into the houseboat's master suite.

Maybe later, in the distant future, Jonny will know sad things, too. Maybe life will someday deal him an eight and a seven instead of an ace and a king. Maybe he will know the frustration of being unable to attain all of his goals, unable to fulfill every dream, having to settle for not being the best. Maybe he will even know what it is to fail.

But before all that, there will be Freddy on guitar and Owen on bongos and Jonny Moseley singing on the deck of the houseboat while two dozen of his friends lie around, sipping cocktails on boats and on jet-skis bobbing in the gentle current, listening to Jonny's song.

��