AS THE DROUGHT of 2000 ground on forever like the invader in some perpetual Eurasian tank war, the forests of the West burned to ash, the broasted air filled with smoke, and everywhere was the growl of bombers flying off to heave slurry at the fires. Tensions, as the anchorpersons say, escalated, both those that sprang from reality and those confected by delusion. In late July, when 350 Hells Angels roared into Missoula, Montana, to party hardy at their annual bash, the chief of police countered with 170 reinforcements. One sweltering night after the bikers withdrew from the bars downtown to the ski hill they’d rented, a phalanx of cops in body armor attacked a noisy crowd of civilians gathered in the smoky streets to let the good times roll and to protest all the cops, and blasted everyone in sight with pepper spray. South of the city a minister’s son, a father of five, was charged with beating to death an older neighbor who had brandished a pistol to illustrate a point about the younger man’s incessantly howling hounds.

For me, these dramas were simply atmosphere, no more than scrim, I admit, for my own private passion play—the simmering feuds with neighbors I’d lived among for a decade, squabbles petty and not so petty that were finally coming to a boil under the weary ocher skies. But such is the nature of what I call the Squalor Zone—the rural sprawl surrounding Missoula and most of our Republic’s cities, that unsavory low-rent sediment layered between suburbia on one side and, on the other, the sweep of farms and big ranches and finally the wilderness—that folks just naturally like to get in your face. The topics of debate are standard: “Resolved: Whereas your [dog, mule, horse, cow, child, fence, hunting ethics, conservation practices, respect for private property] could stand improvement, sir, mine is above reproach. You fucking asshole.”

Even my wife, Kitty, and I had begun to annoy each other by skulking around on tiptoe and checking over our shoulders. The forest at Dark Acres—our little slice of Shangri-la on the Clark Fork River, a five-hour float from the heart of Missoula—is so littered with wind-sheared timber that any combustion in this parched jungle would have erupted into a firestorm consuming our house and shop and corrals. We stopped riding in the forest or putting out our four highbred quarter horses back there to graze because their steel shoes might strike a rock and throw a lethal spark.

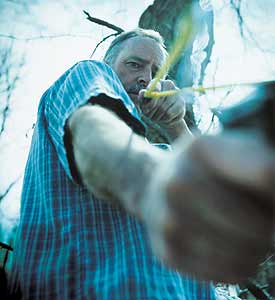

Every afternoon during the peak of the wildfire crisis I shimmied up the angled trunk of a toppled ponderosa to peer through the smoky-yellow glare like a mad gibbon. I issued myself binoculars, a walkie-talkie, a professional-quality slingshot, and a bag of inch-wide stones from the river. At the first sign of fire I would radio Kitty, who was working back at the shop on one of the books she designs for publishers. If I got into a skirmish with a trespasser or spotted one of the many unknown, demented persons who enjoyed reckless gunplay in the ridges above our place, Kitty would call in the sheriff. The slingshot, I told myself, was for protection.

On July 31, when the thermometer hit 100 degrees, I was catnapping in my hammock, mustering the energy for sentry duty, when the shouting began. My first groggy notion was that a neighbor was challenging me to come out and fight. But it wasn’t a feudist causing this ruckus. It was a fire. And it wasn’t the forest that was burning. Under an angry funnel of greasy black smoke, flames were devouring several shacks on a cluttered four-acre tract we dubbed the Rent Trailer, whose owners leased a stained and battered mobile home huddled in a clot of elms to one family after another. The fire had started when a frayed electrical wire jury-rigged from the mobile home to the woodshed had shorted out, showering the shed with sparks.

“Bring more!” Kitty yelled, dragging a pair of garden hoses behind her as she ran down our drive toward the flames.

I did as I was told. By the time I showed up, a disorganized crew of Squalor Zoners had gathered, and they were frantically attempting to connect a series of hoses in order to squelch the fire with water. The trailer was still unscathed, but the flames had leveled two shacks, destroyed an old tractor, and were feasting on the mounds of junk you always find in the weedy yards of netherlands like ours.

The current occupants had escaped unsinged. Mom herded her three kids and a pair of vicious rottweilers into the old family van while Dad saved the chickens and the inferno raged on. A big-voiced four-year-old, whose singing was a daily serenade during happier times, hung her head and wept. We backed away, utterly defeated. In the distance, sirens began to wail.

The next thing that happened was the arrival of deputies and firefighters, speeding up in a dozen trucks, circling the homestead like Comanches in some ancient oater. They doused the inferno in short order and even managed to save the home (whose shell-shocked occupants moved right back in).

I glanced over and caught the eye of Junior Dugan,* a diesel mechanic with whom I had exchanged not one civil word in seven years, not since our bout over zoning featured him in one corner, building himself yet another house on the nine-acre principality of Dugania, facing off against me, a meddler from the property next door, who was lobbying the county to shut him down. Crew-cut and fit, Junior was wearing one of his trademark white T-shirts, still gleaming despite the sooty mess.

Kitty and I stared at the parade of midweek gawkers idling by in their pickups on the county lane. Would Emmitt Hooper show up, I wondered, the retired postal worker with whom I had nearly come to blows over our conflict about water rights? What about C. R. Copeland, the lumber-mill employee who had enraged everyone by erecting a barbed-wire Berlin Wall around a delectable parcel of open range in order to keep his cattle in and the world out? And where was the neighborhood’s loosest cannon, Jay Zank, a chronically underemployed road-construction gofer who trespassed at will by cutting fences, encouraged his bony horses to graze on other people’s pastures, and shotgunned the No Trespassing signs I threw up in defense?

What is it about the Squalor Zone, I wondered, that compels people living here to quarrel all the time? Why does it seem that the chief form of exercise in these pastoral outbacks is jumping to conclusions? After all, each of us has clear title to our corner of the garden that has become the American Dream yet again, the small landholdings that Thomas Jefferson figured would make even the most loutish wastrel a contributor to the commonweal. Is there something about that most counterfeit of vanities—the pride of land ownership itself—that makes us so imperious? Or could it be that all the feuding I’d been party to wasn’t about other people at all—it was about me?

AMERICA’S MOST NOTORIOUS feud was played out in a forested floodplain not unlike that of the Clark Fork. Trouble on the remote Tug Fork River, the border between Kentucky and West Virginia, had been percolating long before Randolph McCoy accused Floyd Hatfield in the fall of 1878 of stealing his hog. But contrary to folklore, the families didn’t take up arms to settle the dispute; they went to court. A jury ruled in Hatfield’s favor, and McCoy abided by the verdict, although he did not accept his defeat gracefully. However, none of the preexisting bad blood (which compelled the judge to stock the jury with equal numbers of Hatfields and McCoys) was spilled until Johnse Hatfield knocked up Randolph’s daughter, Rose Anna. Two years later, in 1882, three of the girl’s brothers murdered Ellison Hatfield on election day. Then the Hatfield patriarch, “Devil Anse,” avenged his brother by executing Randolph’s three sons near what is now Matewan, West Virginia. This blood feud would roil Kentucky and West Virginia for another decade, bring the dispute over borderland jurisdiction to the U.S. Supreme Court, and cost eight more lives.

During the same decade a lethal running battle broke out between cattlemen and sheepmen along Cherry Creek in the Tonto Basin of what is now central Arizona. For years the first cattlemen in these meadows, where grama grass grew to the stirrups of a horse and the ridges were black with heavy pine forest, had vowed that no matter what squabbles arose among themselves, not a single sheep would enter this open range. They looked down on sheepmen and the Navajo herders they employed, and were horrified by the grotesque damage done to other areas of the territory, where sheep had been allowed to graze grass to the nubbin and their sharp hooves had torn up the turf. In 1886, when the biggest sheep outfit in the territory, the Dagg Brothers of Flagstaff, decided to move a herd south over the Mogollon Rim from exhausted pastures, they hired a local clan, the Tewksburys, for protection. Within a year cattlemen had driven the sheep out of the Tonto Basin, instigating a full-tilt feud that would claim the lives of a score of men over the next six years and would become known as the Pleasant Valley War.

Range wars between ovinophiles and bovinophiles would flare across the grasslands of the West for many decades to come. In Wyoming, it’s estimated that in the two-decade period surrounding the turn of the 20th century, raiding cattlemen and their henchmen would bludgeon and shoot to death more than 100,000 sheep. It was predicted that this sort of carnage would occur in the unbelievably rich prairies of Montana, but in fact many cattlemen here were hedging their bets and setting aside part of their range for sheep. Even so, when Kitty was a child growing up in the 1960s on a thousand acres of irrigated Hereford ranch in Montana’s Helena Valley, the frontier prejudice against woollies was still rampant. Every fall when the cattle buyer came to call, Kitty and her five siblings were compelled to hide their 30-head herd of Suffolks—each beloved 4-H sheep bestowed with a name like Stuart, Stanley, or Stephanie—because their presence might make the buyer lower his price for the family’s beef.

Old-fashioned feuding also endured into modern times in the hollows of Greene County, Virginia. The players in this running skirmish were from the Shifflett and the Morris clans, families that had intermarried so often during their two centuries of coexistence in the Blue Ridge Mountains that their surnames were simply formalities. No one knows the origin of the free-for-all—except that it was born from the “Code of the Hills,” a body of unwritten rules about vengeance, vigilantes, and hillbilly conduct holding that, for instance, if you knock up my sister, I’ll burn your house down—but at its most violent it seems to have revolved around moonshining. One early fight, however, was a rock-throwing battle in 1922 over the issue of abusive language. During the next nine years a dozen men were murdered by gunshot or bludgeon, and there were scores of assaults, murders, and weddings. In 1931 a local newspaper, the Daily Progress, reported that “wholesale hot-headed shooting was the order of the day yesterdayÉwhen two men stood face to face and killed each other in a fierce pistol- shotgun duel.” The combatants were Manuel Morris, 45, and Bernard Shifflett, 35. Three bystanders were also wounded in the melee. According to witnesses, Shifflett’s carcass was filled with lead from head to toe. These dysfunctional families were still devouring themselves as late as 1961, when a jury sentenced 40-year-old George Shifflett to 60 years in the state pen for shooting to death his cousin, Eugene Morris, a 38-year-old father of nine, in a dispute about a stolen barrel of corn mash used to make whiskey.

Men learn to quarrel with one another in the same way they learn to sit a horse or talk to a woman; that is, from their dads. The eccentric habits of my father were legendary in the marshy boondocks where he raised me and my sister without the benefit of a woman’s touch, after our mother died when I was seven. We lived on three bushy acres straddling Sand Coulee Creek south of Great Falls, Montana, in a hayseed’s paradise called Rat Flats. Although it was scraped from the Great Plains instead of the Rockies, Rat Flats, which also lay in an economy-class floodplain dotted with shabby, cold-comfort ranchettes, was culturally identical to my new Squalor Zone. The refurbished commercial turkey coop we called home was less than a quarter-mile from the Missouri.

My old man kept chickens and pigs and a horse named Pinky, and for a time he owned part interest in a buffalo named George. He fed his pigs stale doughnuts he fished from bakery trash cans. For his sake it was probably a good thing he had this menagerie to fuss over, to distract him from his darker passions. Besides bars and bar fighting, he also enjoyed spreading roofing nails in the ditches of the county road because he didn’t like the growl of dirt bikes. After shooting a neighbor’s noisome dog he claimed that he was just trying to scare it into silence and it musta hadda heart attack. He regularly strode along the creek and shotgunned crows in the box elders because their cackling put him on edge.

In his later years he sought to augment his civil-service pension with extra cash, so he invested in plumbing and electrical outlets in order to create lots on his front acre for three rental trailers. The neighbors circulated a petition intended to stem the buildup of his rural slum and forced the county commissioners to deny him permission for any hookups. Cantankerous to the end of his life, he trucked three dented mobile homes to his pasture anyway, and parked a couple of his vintage Dodge Darts out there as well. When the neighborhood complained, he gleefully pointed out that since I ain’t hooked up nothin’ no law was broke.

DARK ACRES, SO NAMED because it languishes all winter under a foggy gloom cast by Black Mountain across the river in the Lolo National Forest, had once been part of a fading cattle operation, a century-old homestead cloistered inside a mile-wide loop of the river, whose owners began subdividing their empire in the 1970s. Like Squalor Zones everywhere, this here’s Trailer Country, friend. Most of the structures on our wedges of wooded bottomland were trucked in (I get snooty because our “modular” home arrived in two pieces). In addition to the usual farmy clutter of implements, everyone’s compound sports at least three trucks, plus one or maybe all of the following: a four-wheeler, a snowmobile, a fake wishing well, a trampoline, or a collection of equines and the jumble of shelters and corrals they require.

Outbuildings in the Zone are thrown up without regard to covenants, because there are none, or to zoning. People keep goats and peacocks and guinea hens, and burn mattresses and ruined vehicles wherever, and lurk all fall up a tree with a bow and arrow, waiting for something tasty to stroll underneath.

For a long time the Zone’s ranchettes were outrageous bargains—we bought our house and shop, plus 11 acres of marsh, pasture, jungle, and parkland, in the fall of 1990 for $69,000. Today Dark Acres would net us several times that, but we wouldn’t move back to a city even if someone gave us a house there, and not just because of the organic pleasures of living with horses. The animal freedom to walk out the back door anytime, day or night, to howl at the moon or go for a swim has just become too addicting. Despite its headaches, this place is as close to the rhythms of daily life inside the natural world as most Americans are ever going to get. Once you’re on the banks of the Clark Fork and are dwarfed by the palisades of the Bitterroot Mountains on the other side, you see nothing in any direction of the visually insubordinate work of mankind. It might as well be 1600 b.c. By day the luscious transparent river chatters and rolls stones and dimples in the fading light with rising trout. At night, under a Milky Way so showy you can actually see how it got its name, the leaves of the willows shudder in breezes perfumed with the tang of pine sap and sage.

But there was rancor in paradise the first day we moved in, when our dog Radish, a red heeler, wandered down the dirt road and beat up a chicken named Gary. (A detective at the Missoula County Sheriff’s Department later told me that loose animals are among the most common causes of friction between people in these parts.) I tried to placate Gary’s masters—two brothers named Bunker raising three small boys in a double-wide that looked like it had been dropped from a cargo plane—with a six-pack of Mexican beer and a promise that if the fowl croaked I’d buy them a replacement. When their eyes lit up I deeply regretted this offer.

“Gary’s a hunnert-dollar chicken,” I was informed.

“What!”

“Yeah,” the other brother said. “Gary’s a fightin’ chicken.”

I watched these two yahoos for a week to make sure Gary didn’t have another accident and end up in a stew. But the Bunkers were telling the truth about raising gamecocks for a “sport” that’s not legal in Montana—and the dumb bird pulled through.

AFTER I PUT the matter of Gary behind me, I was soon embroiled in more serious hostilities. As the new lord of Dark Acres, I felt compelled to take on the matter of sprawl in the neighborhood, my position being that there shouldn’t be any more. (It’s always the most recent immigrant who wants to bar the gate.)

One day, when I heard the clamor of pounding hammers coming from Junior Dugan’s place, I strolled over to investigate and discovered that he had dug the foundation for a new house and was busy building a frame, the spring sun glaring off his white T-shirt. I checked the zoning and discovered that he didn’t own enough acreage for another home. When I phoned Junior and informed him of this fact, he replied that because the family’s occupancy on Dugania predated the zoning laws, he could do what he liked. After a local lawyer advised me that there weren’t any grandfather clauses in the zoning system, I filed a complaint with the County Board of Adjustments. The hammering at Dugania abruptly stopped. Junior filed an appeal. One hot night three months later the board ruled 3-0 in his favor. At midnight the lights in his unfinished house suddenly blazed on—a message to me, the new crank on the lane.

Still, the most aggravating of the local government’s failures in the Squalor Zone was its inability to do something about the gunfire emanating from an evil quarry everyone calls the Gravel Pit. Owned by the state but leased to the county, this trashy amphitheater, gouged from a ridge above the river within rifleshot of Dark Acres, has served as a shooting gallery for two generations of plinkers and vandals. We’ve heard automatic weapons up there, Uzis, maybe AK-47s, and watched as tracers cut through the night sky like meteors. Then there were the impromptu “turkey shoots,” that burgeoning Squalor Zone sport in which contestants detonate sticks of dynamite by plugging them with bullets. Occasionally some of these madmen fired at the bottomland, figuring that if it looks uninhabited, it must be. But if you hike up on the ridge and stare long enough you’ll begin to notice signs of life down there, down where we live—horseback riders, dog walkers, firewood cutters, coeds in gaudy float toys, anglers in drift boats, old men on the banks casting for whitefish. Finally some longtime Zoners grew weary of dodging bullets and clenching their teeth from all the noise and circulated a petition demanding that the county enforce its own no-trespassing policy at the Gravel Pit. Everyone was pleased when the county surveyor ordered the construction of a wire fence to keep out the riffraff. But the very night it was finished someone backed up a truck, hooked a chain to a post, and yanked the entire fence right out of the ground.

The trouble at Dark Acres was in the soil, waiting for us long before we arrived. Because swamps divide the place into two provinces it had always been easier for trespassers to access the more distant half of our property than it had been for the residents. For decades the savviest of these interlopers would make three pilgrimages a year to this sweet land for reasons that had nothing to do with the soul. In May they arrived to creep around in the snowberry bushes searching for wild morels. When these mushrooms pop up after a warm spring rain they look like little brains on sticks, and are a savory delicacy in soups or stuffed with wild pheasant. For the first couple years we were so happy to be living in the boonies we never objected when we saw people trespassing with their ubiquitous goody bags. Besides, I didn’t know a morel from a toadstool. But after a friend pointed out one and then another and persuaded me to take a taste I finally understood. We discovered that the richest beds were clustered on the banks of a swamp that we immediately named Lake Morel. The next day while I was riding Timer, our bay brood mare, with Kitty close behind on Rolex, a paint, we came across a middle-aged guy making his way from Lake Morel to his canoe with a pair of bulging pillow slips.

“What’s in the bags?” I asked cheerfully.

He looked at them as if they had just jumped into his hands. “These ones? Oh, heck, nothing much.”

“Here’s the deal,” I advised him. “Don’t come back. Ever.”

The arrogant, self-righteous tone in my voice of the overprotective landowner surprised me. But I had to admit that I liked the way it sounded. In truth, I was full up to here with trespassers who thought they could treat Dark Acres like a public park simply because the tangle of forest made it impossible for us to see them from the house. (It’d be like walking out your back door one day to find a stranger plucking flowers in the garden.)

I looked at Kitty, expecting her to be embarrassed, as usual, by my rude behavior. But she was smiling. Because of all the shooting in the vicinity, Kitty had become even more anxious than me about our animals’ safety. (When Kitty was growing up on her family’s ranch, a trespassing hunter once shot a prized Hereford bull claiming that he thought the behemoth was a deer.) Because Kitty was a cool and collected moral arbiter, she had always impressed me as the voice of reason. So if she decided something could no longer be tolerated, that was the only mandate I needed. Henceforth, I would be unforgiving in my enforcement of a strict no-tread zone around Dark Acres.

Riding alone the next day, Kitty flushed out a thirtysomething couple dressed in shorts and periwinkle pile pullovers hiding behind a juniper. Spooked by their persons, and by the gunnysacks they were hefting, Rolex suddenly shied sideways. When Kitty recovered her composure she ordered the couple to get lost and told them to spread the word that this place was now and forever off limits.

In early July the wild raspberries begin to ripen. Even though the bushes grow in briar patches they share with stinging nettles and hawthorns bristling with spikes, fruit poachers steeled by experience regularly managed to find their way in and out. And when they emerged from this prickly maze with the goods their eviction was swift and sure. Dark Acres, our trespassers were learning, was no longer the neighborhood commons—it was our beloved backyard.

Far more menacing than the produce thieves were the bow hunters who invaded the floodplains those first few autumns to prey on the whitetail herds. Their presence was confirmed by the proliferation of tree stands all along these happy hunting grounds.

When I rode upon the first buck in the fall of 1991, dead long enough to have been stripped by the way of the world, a broken arrow lodged in its bleached shoulder bone, I felt bad for his suffering, but these herds wouldn’t be diminished by his loss. Besides, scavengers need dinner, too. The next season, after we found a doe and then another, both showing evidence of arrow play, I wasn’t so sanguine. As a response to these first dead deer I bought some red-and-white No Hunting signs and mounted them on conspicuous trees. We had debated blanketing our horses with Day-Glo during hunting season, but in the end we simply turned them out into the forest for a few hours, crossing our fingers and hoping our signs would save them from the killer monkeys above. One day during bow season, I went out to bring in the horses and happened to glance up at a ponderosa onto which I had nailed a notice. Perched on his little steel shelf right above the sign was a hunter aged no more than 20. He was dressed in camouflage fatigues and his face was smeared with camouflage makeup. He wore a camouflage hat and camouflage boots. I admired his zeal.

“I see you!” I called out merrily.

“What?” he whispered.

“Get your ass out of my tree and take your spikes with you.”

“What?”

“Here’s the deal, dickhead,” I explained. “I’m going to the house for the chainsaw, and if you’re here when I get back I’m going to cut you down.”

“Is this place posted now?” he asked, feigning innocence.

Maybe I had overreacted to wasted deer or all the gunshots across the river, but again, I liked the sound of menace in my voice. It seemed like a way to scour all the trouble from the soil.

But in the fall of 1995, another dead deer sparked a skirmish that nearly led to open warfare. This time it was a doe, gut-shot with a steel-tipped GameGetter, the wounds as precise as the sutures of a surgeon, punched like crosshairs on opposing sides of her belly. The gluttonous Radish, along with coyotes or foxes, had already eaten into her anus and stripped her gut of all its freshly digested greens, rich with vitamin C.

Whose work this is I think I know.

Seething at the neighbor who, I was certain, had shot the doe across his fence, I walked back up to the house along a canopied path through water-birch thickets to get a rope and a horse.

After I hauled the whitetail into an ancient ponderosa with the help of Timer, I secured the rope to the trunk with a square knot. Suspended there from a limb, the doe transcended the nothingness of death and became a message for the living, fraught with the stark poignancy of Andrew Wyeth’s 1961 watercolor Hanging Deer. Nearby, just across the fence, was another old ponderosa. Spikes driven into the green wood led to a steel tree stand 20 feet up. The sign I pinned to the fence post was brief: “Doe gut-shot by a bow hunter and left on the ground to rot.”

The phone rang a day later. It was my neighbor, Jay Zank, patriarch of Zankland.

“Hey, chickenshit, a real man would come to me first.”

“Real men don’t waste game,” I said.

“It ain’t me!” he shot back. “Them woods are full of hunters. So fuck you, asshole.”

“And the same to you, sir.”

A few days after we raised the dead whitetail I found her carcass on the forest floor underneath the dangling rope, which had been cleanly sliced with a knife. While Kitty took charge of Timer I took charge of the rope, and we soon hoisted this forest billboard back in the tree. Around Thanksgiving, after the first heavy snow, three shotgun blasts and then the whine of a retreating snowmobile shattered the hush. Trudging from the house, I wasn’t surprised to see that my No Hunting signs had been blown away.

THE JEWEL OF THE Squalor Zone, the object of every horseman’s desire, is a 100-acre savanna stretching along the Clark Fork’s eastern shore. When I discovered this grassy parkland in 1993, half of it belonged to a clan named Copeland, which was leasing the other half from the state for use as cattle pasture. Celebrating an intoxicating summer afternoon by floating the river in an inner tube, I had drifted into a trough of whitewater on the far side of what I call Radish Island, the island’s namesake paddling furiously by my side, snapping at the foam. We were hurled into the main channel, and when the current slowed as the water deepened we headed for the bank to catch our breath.

Wandering the game trails meandering through stands of purple willow, I saw that the river had created these grounds for just one thing—riding horses at breakneck speed, something we could do only in short stretches back home because of rocks and tree roots. The river had been thoughtful enough to carve a system of relief channels that run parallel to it for a mile, and had blanketed these serpentine recesses with a cushioning two-foot layer of washed white sand. Riding in these dry washes would give our horses the sort of pumpitude they could only get on a treadmill or at the beach, the edge they need to bring home the money when Kitty competes on them at rodeos and barrel races.

I sat down on a stump ferried here by the floods, while Radish excavated the den of a field mouse, and confronted my own hypocrisy. In order to ride from Dark Acres to the State Land we’d have to cross a piece of private property. I yearned to make this place part of our daily routine because of the great forward motion it would yield, and because I had fallen in love with the illusion that we were living in a less complicated world where we were free to jump on our horses and ride wherever we wanted. But getting a visa would be a problem.

That’s because the land we’d need to cross was owned by Emmitt Hooper. Our relations with Hooper had been less than cordial from the start, when he had stormed onto Dark Acres the autumn we moved in to yell about my leaning of branches against the wire dividing his place from ours. I explained that I was trying to keep down our vet bills by reducing the exposure of horseflesh to barbs, and hello to you, too, neighbor.

But now we’d have to give Hooper something for allowing us to put a gate in that very fence. I was willing to bribe him, but first I’d try to get what I wanted for free. What he asked for was our permission to let archers enter Dark Acres to chase down wounded deer. We knew Hooper resented the deer for stealing his heavily irrigated grass from a dozen mangy, low-bred sheep he owned. So we weighed our contempt for bow hunters against our sudden affection for the State Land and agreed to give Hooper what he wanted. Then, pushing our luck, we went to C.R. Copeland, the lumber-mill worker, and got permission to ride on his property as well.

Kitty and I saddled Timer and Rolex and rode from our corrals to Copeland’s farthest corner, a sandy peninsula on the mouth of a placid riverside slough that I had named the Mabel, after my grandmother. Turning for home, we opened the throttle. Timer glanced back to see if I’d lost my mind, then got so excited she started her gallop with a buck and a fart. As we shot along the beach and turned inland for the savanna she pivoted her ears to listen for the familiar whoa that always reeled her back to earth just as she was starting to have fun. Radish couldn’t keep up with us now and began barking in frustration, his yap fading as we distanced him. After Kitty entered one sandy wash and I rode into its parallel twin I glanced over to see her disembodied blond head skimming just above the ground at 30 miles an hour. We shot from the washes onto a sandy beach through a thicket of willows, and I put my forearm over my eyes to shield them from slapping branches. Finally, as we trotted into our own pastures and slowed to a walk, everyone was winded and trembling and bathed in a righteous sweat. When Radish showed up for the apple all the animals get after a good ride we stood in a circle—woman and man, horses and dog—glowing with endorphic well-being, smiling the smile that says, this is so worth the hassle.

And so for several years our ride to the mouth of the Mabel became a fixture at Dark Acres, something we did almost every day.

IN OUR TENTH SUMMER at Dark Acres the water war began. When we bought the place, which came with irrigation rights to the river, we also acquired water rights to the Mabel. Our portion of this marsh had been partially dammed in 1971 to create a reservoir for thirsty cattle. But over the decades it had been hopelessly clogged with tires, farm implements, rotten hay, and dead animals. After I finished cleaning it, which took three years, we not only had a trophy skating pond, but a whole community of wildlife began returning to its former haunts. And the babbling of the Mabel through a steel culvert in the earthen dam was a sweet sound indeed.

Emmitt Hooper did not share our pleasure. As the endless drought baked Montana, the Mabel’s seemingly inexhaustible flow dwindled. One day Hooper paid us a visit to demand that we hire a contractor to extract the old culvert and bury a new one deeper in the dam. The new culvert would send more water to his place, but it would completely drain the Mabel. Since Hooper was allowed to irrigate from the river, just as we were, I didn’t see the point of ruining our sumptuous, restored wetland just so his mangy sheep could have even more to eat. I did nothing, hoping Hooper would go away.

As the Godfather said, I tried to get out, but they kept pulling me back in. One morning in the winter of 2000, Radish wandered over to Copeland’s place and discovered a dump full of his favorite thing besides bananas—animal parts. He came home so bloated he waddled, and as I put down a bowl of water for him in the yard he barfed. In the vomit were crushed bones and two halves of a cow’s ear. Radish the garbage hound, whose appetites compelled him to sit under our apple tree for hours in the fall barking at fruit in the hope it would drop, gorged at the dump whenever he could, filling the house with night smells that yanked us awake, seized by the conviction that the septic tank had burst. I could have chained him up or run to town for a kennel. Instead I called the county health department to see if property owners are permitted to warehouse rotting flesh on the back forty.

“No, it’s not legal,” a field agent from the health department told me. “It’s a health hazard.”

Not many days later I walked to the dump to fetch Radish and found him staring at the place where his beloved offal had once been strewn. “Please accept my condolences for your loss,” I said, directing him home. The county had ordered Copeland to clean up the mess.

When the ground thawed that spring, the hills were alive with the sound of Copelands pounding on steel posts. Within 48 hours the clan had strung a four-wire fence bristling with No Trespassing signs from the river to the road, almost a half-mile of barbs. Although Zoners everywhere will hotly defend their right to fence out the world, they’re never happy when someone else does it.

Then, one hot night in June 2000, Hooper showed up at our door to deliver his water demands again. The Squalor Zone is not the sort of place where one arrives unannounced (no Welcome Wagons have ever brought around fine products from local merchants, and not one child has ever braved our darkened drive to come begging at Halloween). So when Radish began to howl his Intruder! howl, I reached for the nearest weapon.

“I’m telling you again, dig up that culvert!” Hooper demanded when I threw open the door.

I showed him my old Ping five-iron. “Don’t come back here,” I said, adding, “You idiot redneck jerk.”

He retreated, with me on his heels, down our long lane, through our fence, and back into his pickup parked on the county road. As he drove off, we exchanged more pleasantries, and flipped each other off.

And so it was that by the late summer of 2000 all relations between Dark Acres, on one side, and Hooperland, Zankland, Copeland Land, and Dugania, on the other, had been severed. The balkanization of the floodplain was complete. Were there ambassadors, they’d be recalled. Not only were we barred from Copeland Land by his barbed-wire Berlin Wall, but Hooper, still smarting from our fight about water, had banned us from his property as well, which meant we could no longer run our horses along the river. We felt like we had lost a loved one.

While the drought wore on and temperatures rose I began interpreting natural events as avatars of doom. The herbs in my kitchen garden starting bolting faster than I could pinch off the seeds. The cottonwood leaves turned yellow and dropped. One afternoon I ran back to the forest when I heard screeching and found a red-tailed hawk fighting in the middle reaches of a cottonwood with a gargantuan raccoon. When the coon’s weight snapped a branch he fell soundlessly, hit the ground, bounced, and hit the ground again. I assumed he was dead. Poor little fella, I thought. But as I approached him he shook his head, hissed like a cat as he feinted angrily in my direction, snatched up the whitefish he’d won in the fight, and vanished with an indignant snarl into a briar patch of hawthorns.

ON THAT TEMPESTUOUS day of the fire at the Rent Trailer I found myself thinking about my old man’s seething inner world and wondering if the dark side of his character might have been reincarnated in his bellicose son. Looking back at a decade of acrimony, I sensed that if I were ever compelled to defend my own incendiary behavior before some celestial judge, there’s a chance I might need a lawyer. Maybe I was daft from all the smoke in my lungs, but I decided on the spot that in order to gauge how good this lawyer ought to be I would go to my neighbors, waving a white flag, and ask them to tell me their side of the story—no matter how bad their version of events made me look. Nothing would be lost, although it was possible that I would make a hasty exit stage left, my butt peppered with rock salt. But perhaps a bold move like this would write the postscript to our feuding, freeing all of us to concentrate on saving our places from a disaster like the one before us now.

The next morning I called Junior Dugan, my old adversary in our feud over zoning.

“Don’t think of me as someone you’ve had a quarrel with,” I told him. “Think of me as a reporter. It’s a chance to say what you want to about that jerk down the road.”

Ol’ Junior found the idea amusing. But decided against it. “I think it’s better to just put it behind us,” he said.

“Because you won?” I asked.

“Because I have nothing more to say.”

I gave up trying to get more, wondering what I was missing. I ordered a transcript from the hearing that allowed Dugan to finish building his house. And there it was: The county health department had screwed up by issuing him a septic permit without asking to see a zoning permit. If the Board of Adjustments had turned down his appeal he could have sued them from here to Sunday.

Next I called C.R. Copeland, who agreed to talk to me face-to-face. Sweating on the drive over, I wondered again what the hell I was doing. But Copeland, who was recovering from food poisoning, moved carefully and talked quietly. He said his decision to fence the whole of Copeland Land was the result of years of abuse. Trespassers used to drive trucks onto the place to build bonfires and shoot guns and party and harass his cattle. “Went down there one day,” he said, “and there was a lady roping my calves. ‘I ain’t herdin’ ’em,’ she says. ‘I’m just practicing roping.'”

Although members of his clan objected, C.R. had allowed people such as me and Kitty to ride on Copeland Land if we got permission. But he was finally pushed too far the day he confronted Jay Zank, trespassing, mounted on one of his worthless horses. As Copeland recalled, “He said, ÔI’m going riding over on the river and you can’t keep me out.’ And he told me to fuck off. But he was right. If it’s not fenced you can’t legally keep somebody out. Because they don’t know where the line is. Now they do.”

I looked at him. “I’m going to tell you something that might piss you off.” Bracing for the worst, I said that it was me who ratted him out to the health department about the dead pile. But he already knew—after all, people in the Squalor Zone talk, and very little remains secret.

“What do you think about me doing that?” I asked.

“If you had come to me and discussed it I would have picked up that stuff or buried it,” he replied reasonably.

And that was it. No heat, no oaths, no payback. I was vaguely disappointed. After we commiserated about assorted local irritants such as the Gravel Pit—C.R.’s irrigation pipes had been shot, and he’d found bullet holes in the door of his shop—he told me he was currently feuding with a neighbor whose dog he’d shot because it was attacking his calves. He said he’d complained to the owners about this animal’s predation and made certain they understood what could happen. After he had dispatched the cur, his neighbors called the sheriff, who confirmed that Copeland was legally entitled to protect his herd.

Ah, I thought, will the circle of spite ever be unbroken?

Next I tried to get Zank’s side of the story, but he wouldn’t agree to talk. In fact, he wanted to scream: “You’re pushing your goddamn luck, asshole!” I tried to keep him on the line, but he finally slammed down the receiver so hard it made my ear ring.

Before I visited Emmitt Hooper, I picked a box of Goodland apples from our tree to bring as a peace offering. Tensions had already eased considerably; the Mabel was now gushing with more water than we had ever seen during the summer. But Hooper had not forgotten the night of our fight.

“You come out the door like a raving maniac,” he told me as we sat in his living room. “All you would have had to do was to say I don’t have time to talk to you right now.” Still, he advised me that if the flows petered out again I would have to lower my culvert, implying that he would have no choice but to employ the power of the state to bend me to his will.

So why didn’t he avoid all this trouble and just irrigate from the river, I asked.

“Oh, I used to do that,” he said. “Had a gas pump down there. But someone kept putting sand in the engine and wrecking it.” As I headed toward my truck I asked him what he spent so much time working on in his shop. “Toys,” he said. “Wooden trains. You know, for the grandkids.”

ON LABOR DAY the skies opened and the fires of western Montana finally died out. In October more than twice the normal amount of rain fell down, and the drought seemed at an end. I figured maybe this combustible season in my relations with my neighbors might have ended as well. C. R. Copeland kindly offered to let us ride again at Copeland Land, if we would come to him for a key to the padlock on his gate. We worked on our fences and on a stone wall we were building from river rocks, and a sort of peace returned.

With no feuding duties to occupy me, I set out to get the official line once and for all about who has the right to do what in the Squalor Zone. But the Missoula County Attorney’s office never answered my letters and lists of questions about the rules relating to dogs, fences, guns, and weeds. I was dismayed by this silence, but not surprised. It confirmed my lifelong belief that when it came to rendering services, the law preferred the Squalor Zone to render unto itself. I decided that in a perfect world a handbook of laws and customs would be issued to every address outside the city limits, a Fodor’s guide to the Squalor Zone that your realtor would give you the day you moved to the country.

I had better luck getting answers from Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, which confirmed that folks in the Squalor Zone can pretty much do what they want in regard to the discharge of firearms on their own land; that bow hunters must get permission to chase bleeding deer onto private property; and that the state’s Stream Access Law says you’re not trespassing as long as you are a recreationist who confines your person to land below the high-water mark. Then MFWP’s information officer scolded me for denying hunters access to Dark Acres. “You wouldn’t be considered a good conservationist,” he said. “Allowing an animal’s meat to go to waste is hard for someone in my position to understand.” He said that in Missoula County there are only two effective ways to control the deer herds—hunting and vehicle collisions. Without these governors, he said, the whitetail population would explode, animals would run out of food and starve, and the mountain lion population would also explode. Did we want to live in a place where dogs and children were no longer safe? Of course, the MFWP man doesn’t have to live with the gaseous outrages of Radish, nor does he apparently worry about our horses becoming equine pincushions. But I got the point.

In these kinds of disputes, he concluded, “It is often the case that neighbors just don’t like each other.”

Winter approached, and I heard on the grapevine that Emmitt Hooper was planning a lawsuit intended to drain the calming and innocent water of the Mabel, which was about to harden into my favorite ice-skating pond. One chilled and rainy morning, I led Scarlett, my palomino mare, to the forest so she could browse on the last of the season’s grass. As I passed by the Mabel I stopped to watch a mated pair of mallards swimming in the rain, growing fat and glossy before they winged south for winter vacation.

Then a shotgun blast shattered the peace. I put Scarlett back in her corral and ran toward the disturbance, ready for battle, not thinking straight even after all the steeling I had experienced from the conflict of the last decade. There on the river was a tiny island of reeds drifting languidly in the mist. Although I knew that what I was seeing was just a kid duck-hunting in a floating blind he had gone over the top to build, in the water-colored light this graceful vessel looked like something from a Viking funeral, a craft that ferries the soul. I had the sudden sense, which must come at last to everyone, that the days are truly numbered. Did I really want to spend this dwindling allotment of time feuding with my neighbors?

None of us should even be living here, I thought. The economic system that allowed individuals to own land in a floodplain was corrupt. These corridors along our rivers should be held in common so a person could walk unimpeded the length of the Missouri, or embark on a horse trip from Missoula to the Pacific without rednecks yelling to get the hell off. The only reason any house was allowed to be built at Dark Acres at all is because the original owners hauled in enough fill to build a terpen, an artificial hummock engineered by ancient Celts and used by the early Dutch to make sure their churches stayed above the North Sea when it flooded. And yet, even though the Squalor Zone is crawling with so many of the unglued they could pack an auditorium full of anger-management patients, this is the best place I’ve ever lived.

And until they pry my cold, dead fingers from the deed, I’ll never give it up.